Alder Sumer lay in lower Mesopotamia, an arid land broken by belts of green along the banks of its canals and waterways and, to the southeast, the marshes and islands of the Shan al-Arab delta (see map on p. 3). Sumer was occupied as early as the 7th millennium BC. By 2500 BC it had become a land of remarkable agricultural and material wealth. Over the millennia, settlements multiplied and grew in size and complexity, from simple agricultural villages to full-fledged cities.

Museum Object Number(s): B17693

Except for its agricultural and pastoral potential, Sumer was a land of few natural resources and depended on outside sources for many of its goods. A lively international trade connected it with other lands far across the mountains and seas and provided the ingredients for a highly developed commercial, cultural, and artistic life. The inhabitants spoke Sumerian, a language with no known relatives, living or dead. With it, they developed the world’s oldest writing system in a script we call cuneiform. For the first time, if still dimly, written records illuminate archaeological remains.

This era of Sumerian ascendancy falls in what we call the Early Dynastic period, comprising the first half of the 3rd millennium BC. It was a period of great importance for the history of all Mesopotamia, which lay at the brink of empire_ While times were prosperous they were not always peaceful. Independent, warring city-states rose up and fell from power. One of these was the great city of Ur, located on the banks of the life-giving Euphrates River.

Museum Object Number(s): B17167

Ur and the Royal Cemetery

Field research by the Joint Expedition of the British Museum and the University of Pennsylvania Museum in the 1920s provides an unusually complete archaeological picture of this major center (see box on The Royal Cemetery). It was founded sometime in the 4th millennium BC and occupied for perhaps three thousand years. Its strategic location on the Euphrates, with waterway access to the Persian Gulf, helped it grow by the 3rd millennium into a major, fully urban center. In the Early Dynastic period it was ruled by kings whose names and successions we can only partially reconstruct from spotty and inconsistent written records. We do know that, like other Mesopotamian city-states, it had a deity—the moon-god Nanna—upon which its prosperity depended; religion and the state were closely enmeshed.

After only a short period of archaeological exploration, Ur offered up a most spectacular find: the vast cemetery in use at the peak of its early prosperity, around 2650 BC. Some 1850 burials were excavated, most of them simple inhumations. Sixteen, however, stood out for their distinctive construction, the wealth of their contents, and the fact that they included the remains of attendants who were buried with their masters to serve them in the Beyond as they had in the Here and Now. Leonard Woolley, the Director, deemed these extravagant tombs “royal.” We still call them royal although few have been unambiguously identified as such by written evidence. The deceased may have indeed been royal, or they may have been important personages in the temple hierarchy. Or perhaps they were both, a combined role known from cuneiform texts and a reasonable assumption in a society in which the temple and the palace were so closely linked.

Museum Object Number(s): B16710

Museum Object Number(s): B17691

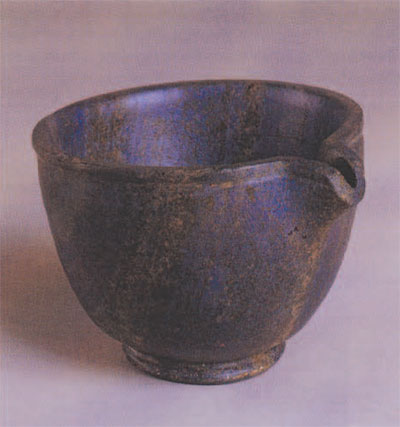

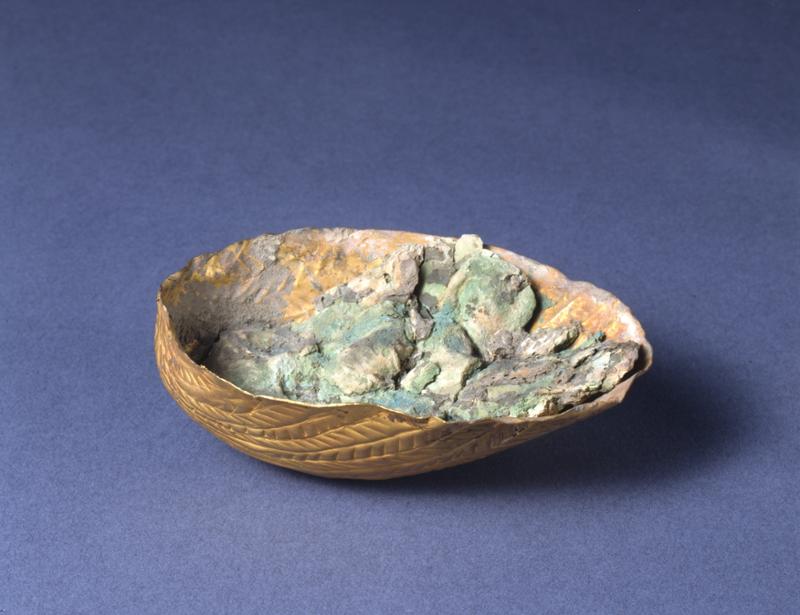

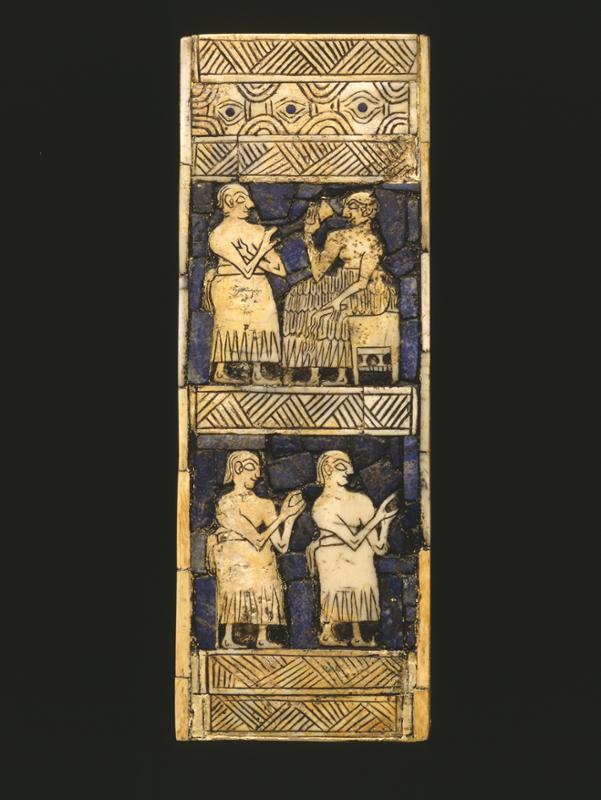

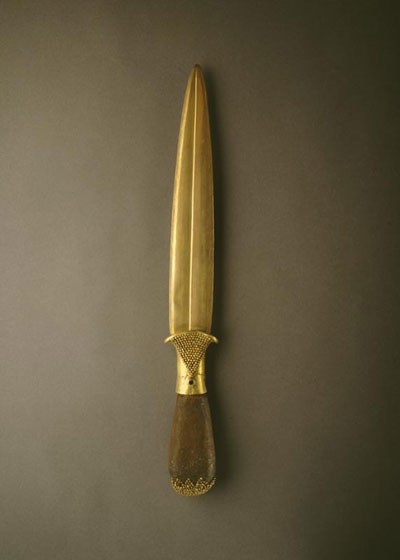

The royal burials contained riches almost beyond imagining—gold, electrum, and silver; lapis lazuli, carnelian, agate, and chalcedony; carved and decorated vessels of precious metal and semiprecious stone; tools and weapons in precious metals; jewelry and personal belongings, even cosmetics. And, to the wonderment of both scholars and the public, each tomb contained from a half dozen to several score of retainers’ bodies, dead apparently by their own hands.

Unfortunately, most of the tombs were looted of their contents in antiquity or disturbed by later burials cut down through them. However, one of the most lavish and intact examples-PG 800, that of “Queen” Puabi-is the centerpiece of the University of Pennsylvania’s holdings. Puabi, identified by a lapis lazuli cylinder seal bearing her name, was clearly a woman of extraordinary importance in her day. Her tomb contains not only a wealth of material but a wealth of information about the time and place.

Woolley vividly reconstructed the elaborate funeral ceremony on the basis of her tomb and one that lay below it. In the first phase, the royal body was carried down a sloping passage and laid to rest in the burial chamber, usually on a wooden bier or in a wooden coffin and always with all the finery at his or her command. Three or four of the deceased’s personal attendants lay nearby. This phase of the ceremony finished, the chamber door was blocked and plastered over. Then, in the words of the excavator, Down into the open pit, with its mat-covered floor and mat-lined walls, empty and unfurnished, there comes a procession of people, the members of the dead ruler’s court, soldiers, men-servants, and women, the latter in all their finery of brightly coloured garments and headdresses of carnelian and lapis lazuli, silver and gold, officers with the insignia of their rank, musicians bearing harps or lyres, and then, driven or backed down the slope, the chariots drawn by oxen, the drivers in the cars, the grooms holding the heads of the draught animals, and all take up their allotted places at the bottom of the shaft and finally a guard of soldiers forms up at the entrance. Each man and woman brought a little cup of clay or stone or metal … (Moored 1982:74-75)

The little cups held the poison that promised their bearers safe journey into the Underworld where we suppose they would continue to serve in the court of their masters, but it is also possible that they and the other contents of the tomb were intended as gifts to various Underworld deities. In any case, such collective burials are unknown anywhere else in Mesopotamia (excepting a possible reference in a text from Lagash) either before or after. Much about them remains puzzling. What remains brings clearly to view the material brilliance of Sumerian culture and society.

Museum Object Number(s): B16692

Museum Object Number(s): 30-12-714

Museum Object Number(s): B16691

Museum Object Number(s): B16685

Museum Object Number(s): 30-12-697

Museum Object Number(s): 30-12-573

Museum Object Number(s): 30-12-696

Aftermath

In the second half of the 3rd millennium, Ur’s ascendancy was eclipsed by the rising power of a rival center, Lagash. Shortly thereafter, Sumer and its cit-states fell to Sargon I, the conqueror who unified Mesopotamia for the first time by creating the Akkadian Empire. The city celebrated a brief resurgence of power at the end of the millennium under the Third Dynasty, founded by Ur-Namma; during this period, the massive ziggart of Ur was raised. After being sacked by the Elamites, Ur was rebuilt under the dynastic rule of the cities of Isis and Larsa. But it was never to regain the prominence it once had, even under the relative prosperity of Babylonian (18th century BC) and Neo-Babylonian (6th century BC) rule. By the time of the Persian Empire, the collapsing city had little to show for its past. No doubt the shifting course of the Euphrates contributed to Ur’s demise, for the abandoned site now lies some 10 miles away from the riverbed. The river that gave it life may have also dealt the final blow.

Museum Object Number(s): 30-12-484

Museum Object Number(s): 30-12-550

The Royal Cemetery

Excavation and Exhibition

The site of ancient Ur has been part of the archaeological map of Iraq since the mid-19th century. It was explored first by the British Museum and then, late in the century, by the University of Pennsylvania Museum. The site continued to hold the interest of both institutions through the disturbances of World War I and its aftermath. When Iraq reopened to archaeological exploration in the 1920s, the Joint Expedition of the British Museum and the University of Pennsylvania Museum quickly stepped in, with British archaeologist C. Leonard Woolley as Director.

In spite of general enthusiasm for the site, no one, not even the Director, was prepared for the unparalleled splendors that were to be unearthed. In fact, so unprepared was Woolley that when he started turning up quantities of gold beads in the Cemetery area in 1922, he wisely decided to delay excavating until his workmen had cut their teeth on less demanding areas of the site. As a result his carefully excavated and well recorded findings, and his skill at reconstructing his finds, stand as a technical achievement that continues to provide, seventy years later, material for analysis and reanalysis.

Soon after excavation, the finds from Ur were divided among the three interested parties: Iraq, the British Museum, and the University of Pennsylvania Museum. Objects from the Royal Cemetery have been on display in the University of Pennsylvania Museum since their arrival in Philadelphia in the 1930s. Now, for the first time, the finest of these will be displayed together outside the museum in an exhibition entitled “Treasures from the Royal Tombs of Ur.” This article provided a preview of the exhibition’s Treasures.

Museum Object Number(s): B17166

Further Reading

Dyson, Robert H,. Jr. (selected by) 1977. “Archival Glimpses of the Ur Expedition in the Years 1920 to 1926.” Expedition 20(1)

Expedition Magazine 1977. Special Issue on the Ur Excavations. Expedition 20(1).

Kuhrt, Amelie 1995. The Ancient Near East c. 3000-330BC. Vol 1. London: Routledge.

Moorey, P.R.S. 1977. “What Do We Know about the People Buried in the Royal Cemetery?” Expedition 20(1)

Moorey, P.R.S 1982 Ur “of the Chaldees.” A revised and Updated Edition of Sir Leonard Wolley’s Excavations at Ur. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Zettler, Richard L., and Lee Horne 1998 Treasures from the Royal Tombs of Ur. Philadelphia: The University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology.