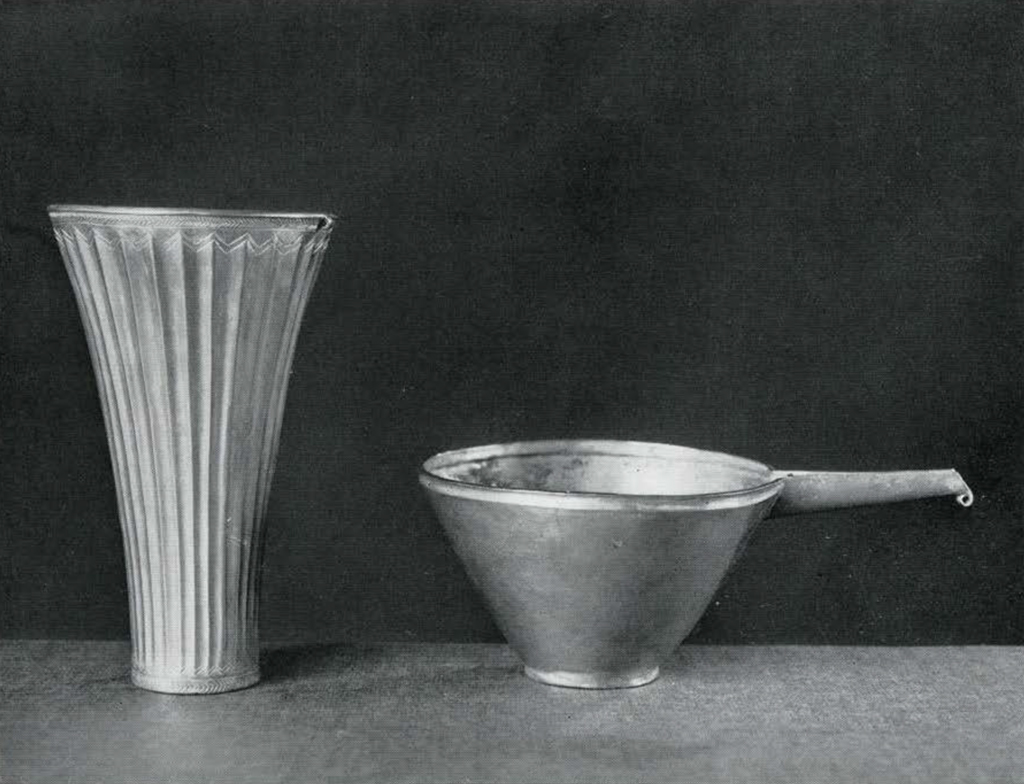

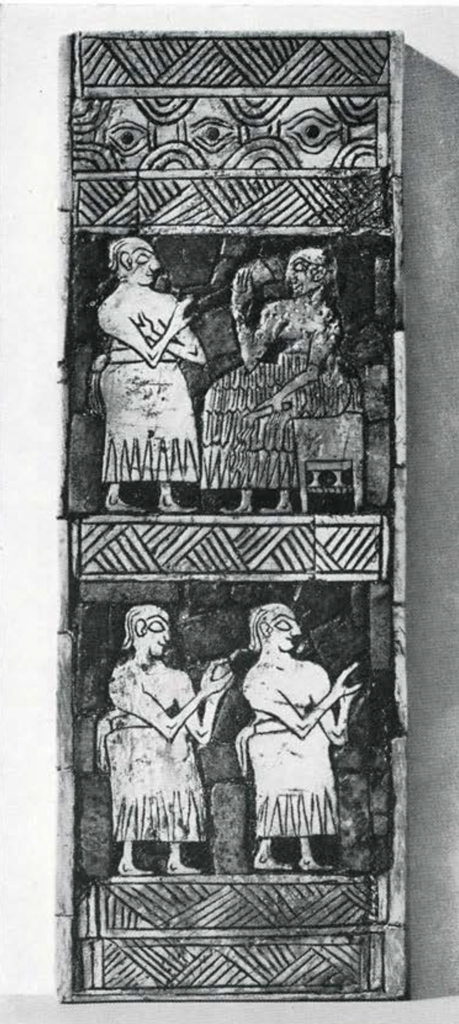

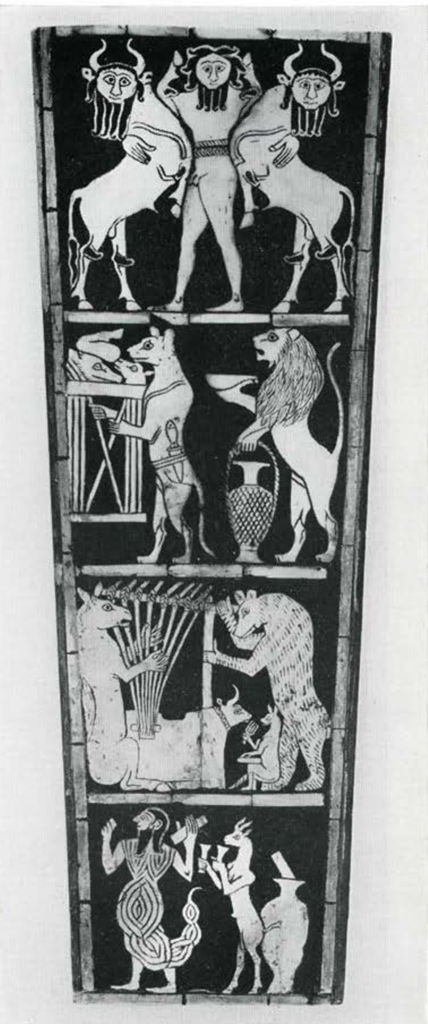

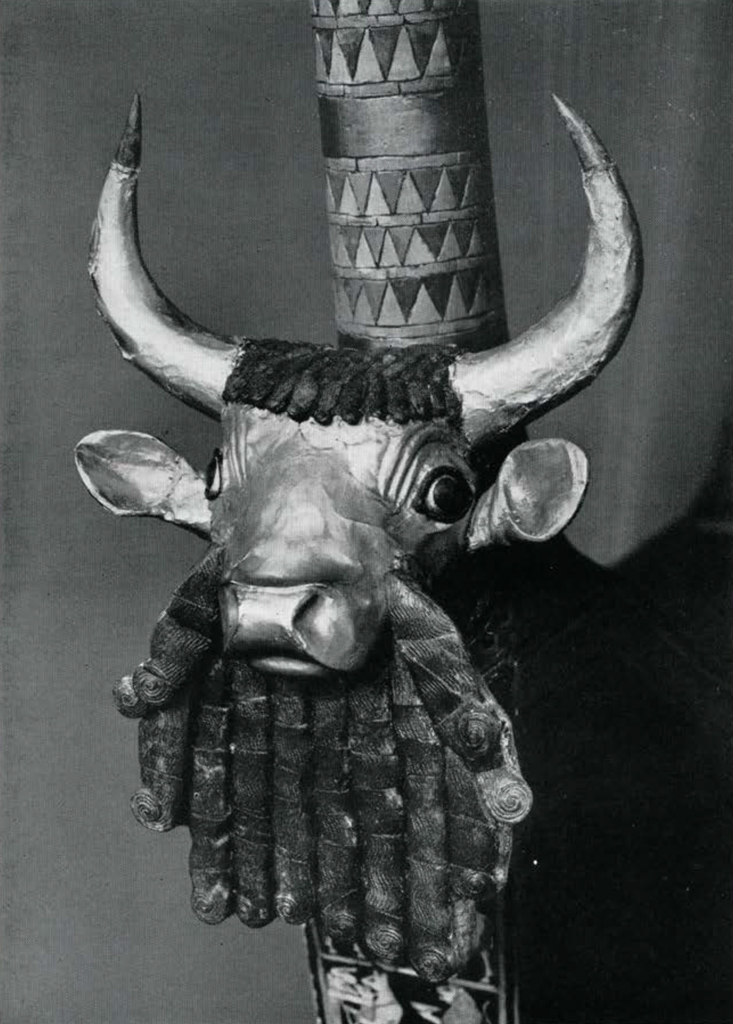

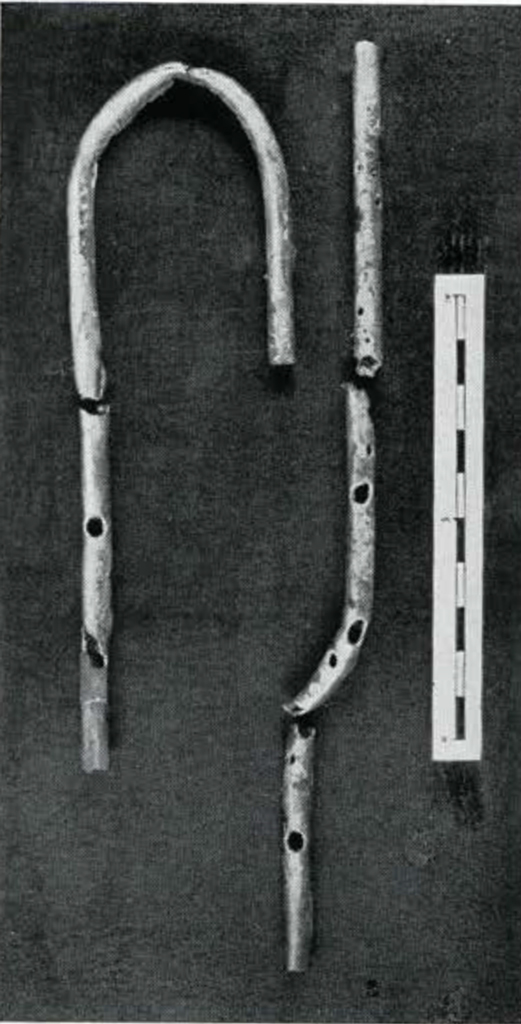

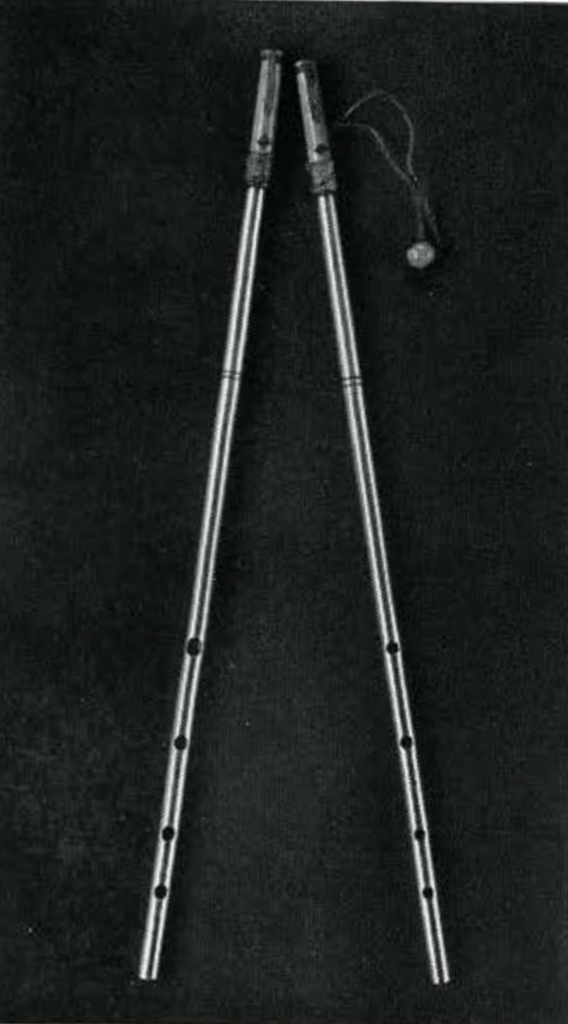

While the Nippur Expedition (1888-1900) was entirely supported by the Public-spirited Gentlemen of Philadelphia and the University of Pennsylvania, the expedition to Ur of the Chaldees (1922-34) was undertaken by the joint efforts of the British Museum and the Museum of the University of Pennsylvania. The site had been identified in 1854 by Taylor. In 1899 a committee was formed in Chicago under W. H. Harper with a view to excavating it more completely, but the request for permission to excavate was not granted by the Turkish authorities. It was the good fortune of H. R. Hall to open the new trenches at Ur and in a small neighboring mound, soon to be famous, al-‘Ubaid, in 1919 on behalf of the British Museum alone. The work was resumed in 1922 by Mr. (since Sir) C. Leonard Woolley, director for the Joint Expedition of the British Museum and the University Museum. The more important results have already been published in six volumes, two of texts: Royal Inscriptions (1928) and Archaic Texts (1935); four of archaeology: al-‘Ubaid (1927), The Royal Cemetery (1934), Archaic Seal Impressions (l 936) and The Ziggurat (1938), the last three with a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York. They illustrate the brilliant discoveries made at Ur, notably in the Royal Cemetery, whose treasures fill one room of the Babylonian Section. For beauty and interest these remains of the early dynastic period of Sumerian art and culture are unsurpassed. Strange funeral rites and human sacrifices add to them a gruesome note. When Queen Shubad was buried in state, she took with her in the large shaft dug about her tomb her chariot with the team of asses and the three grooms, the six bearers of the golden lances, her women singers and lyre players together with their instruments, all adorned with their gold crowns and court dresses, her gaming boards, her wardrobe, her vessels of gold (Figure 9), silver, copper, calcite and soapstone, her jewels and ornaments, gold comb, hairband, crowns, lunate earrings, inlaid finger rings, cylinder seals of gold and lapis, and her treasure of beads of gold, silver, carnelian, lapis and onyx, of all shapes and colours, her vanity case, her gold and silver powder boxes (see title page) and shells filled with stibium and green paint. Gold and silver heads of bulls and lions (see page 2) in the round decorated her throne and sleigh and the sounding boxes of the lyres. From other royal graves came solid gold daggers with lapis handles, the golden cups engraved with the name of King Mes-kalam-dug, and the famous Mosaic Standard on which scenes of peace and war are richly illustrated in six registers of small figures of shell on a blue lapis background. Mosaics (Figures 10 , 11 ) also decorate gaming-boards and lyres. An especially interesting panel of animal figures is seen under the gold and lapis bull’s head of the University Museum lyre (Figure 12). Another lyre of silver plated over wood, in the shape of a boat (Figure 13) with a stag bounding in front amidst the reeds of the marshes, shows the same skillful blending of grace and strength. There is, besides the lyres, a relic which is at present unique and which bears an irrefutable record of the musical system of the Sumerians in the third millennium B.C. This is the twin silver pipes of Ur (Figure 14), first recovered and restored at the Museum. Each pipe has four equidistant finger holes. Modern copies made in silver and provided with a split reed mouthpiece (Figure 15) have sounded sweet tones, and open a new field to theories about scales and counterpoint (cf. Music of the Sumerians, Babylonians and Assyrians by Francis W. Galpin, 1937; The Greek Aulos by Kathleen Schlesinger, 1938). Other curious objects are filigree work in gold and silver, a gold cup in the shape of an ostrich egg; gold and lapis pipes used as a straw to drink beer or wine; a lapis lazuli libation cup and a whetstone; a copper shield with lions and rosette in repousse work (Figure 16) which seems to herald Assyrian art. Two skulls, one of a court lady, one of a soldier of the bodyguard, have been lifted intact as they originally lay in the tomb shaft. One shows the court headdress, comb, gold band, crowns, earrings, necklaces, the other the copper helmet crushed under the reed matting and accumulated earth which filled the shaft.

Museum Object Numbers: B17691 / B17692

Museum Object Number: 30-12-484

Museum Object Number: B17694A

The rampant goat in the bush (Figure 17), a composite statuette made of gold, silver, lapis lazuli and shell, is the most beautiful object recovered in the Royal Cemetery. The he-goat – the ram of the goats – is about twenty inches high, reared on his hind legs. Head and legs are of thin gold, plated on a wooden core. The belly is silver-plated. Spiral horns, eyes and shoulder fleece are made of lapis lazuli, the body fleece of white shell. The tree, leaves and rosette flowers are of gold. The pedestal is of silver with a mosaic panel of shell, lapis lazuli and red limestone. The gold socket rising above the shoulder shows that the statuette was not free sculpture, but applied art, the decoration of a piece of furniture. Our example is one of a pair; the other is in the British Museum. It was probably the support of an offering table, the Sumerian “cane-altar” as represented on a seal in the Berlin Museum (cf. Museum Journal, September-December, 1929, p. 234-35), where a bull rampant figures in the same position. Bread and wine cups are deposited on it in front of the enthroned god. The Hebrew tradition has preserved the memory of gold altars to offer incense in the temple. The gold altars of Babylon are described by Herodotus. They may be traced back to the almost prehistoric Sumerian goldsmiths and lapidaries. Their refined art, their love of contrasting materials and colours, their subtle elaboration of details are most characteristic evidence of the high degree of their civilization. The goats rampant were found in the large tomb, together with the four gold and silver lyres, one wagon, and the bodies of thirty-four court ladies, wearing their full regalia (cf. The Royal Cemetery, pp. 264, 301 and Plates 87-90).

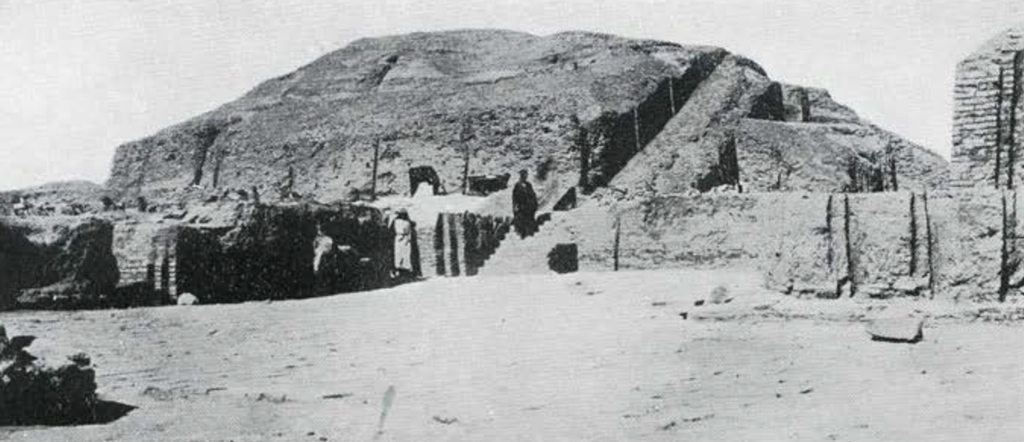

Many seals have come out of the royal tombs, some bearing royal names. The engraved scenes richly illustrate the daily life and artistic inspiration of the period. Seal-impressions are found mixed with them. The bulk of the more archaic belong to an earlier, the Jemdet-Nasr period, as will be seen later. The Ziggurat, the great stage tower of Ur (Figure 18), as it stands today the best preserved tower of southern Mesopotamia, is a construction of much later time, built by the kings of the Third Ur Dynasty, as will be mentioned in its place.

Museum Object Number: B17694B

Museum Object Number: 30-12-253

Museum Object Number: B17066

Image Number: 8090

Museum Object Number: 30-12-702