One of the most important pieces of Greek sculpture that has come to America in recent years has just been acquired by the University Museum. It is a stele or grave relief, and belongs to a class of monuments which, like our modern tombstones, were erected in memory of the dead to mark the places of their burial. Such monuments are today rarely met with in museums outside of Greece. Their size and, on the whole, their general excellence, make them much prized by the archeologists of Greece, and by all who are interested in the history of art.

This stele is roughly 1.55 meters high and 90 centimeters wide, the typical size of the best of these monuments. It is of Pentelic marble, which has turned to a deep brown. This patina is unusually good, and rich. The stele has been split in two, and I fear that this was done intentionally: fortunately, however, the two parts join quite perfectly in front. Underneath the chair of the seated figure there is an old break and a fragment is missing.

Museum Object Number: MS5470

Image Number: 3319

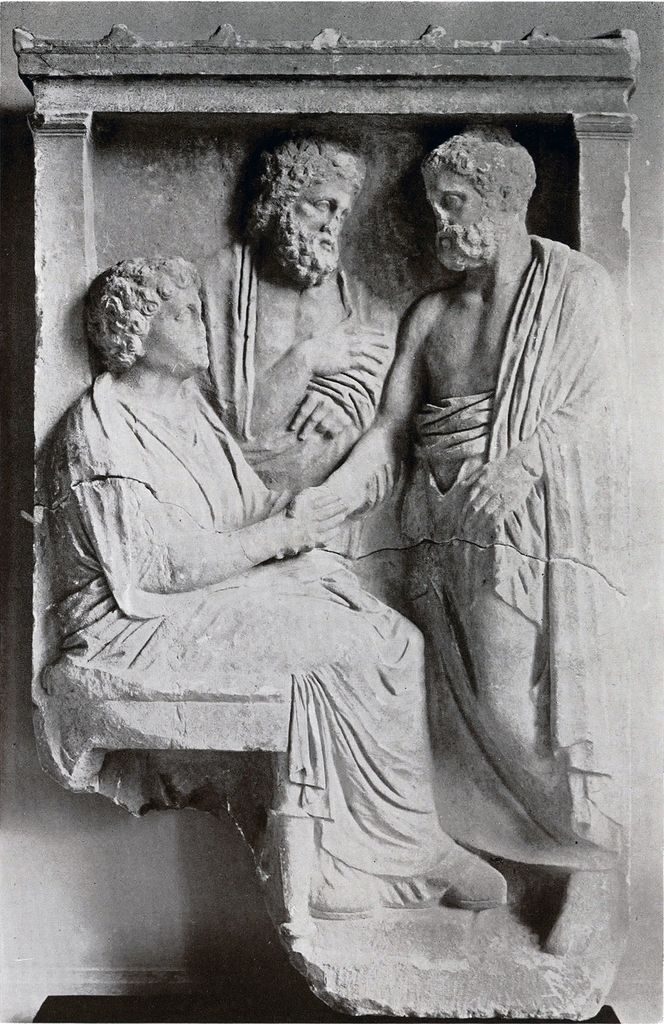

The subject represented by the sculpture is one not uncommon among these grave reliefs. A woman, seated in a straight chair, holds the hand of a man who stands in front of her. This woman is the deceased, over whose tomb the monument was placed. Her face wears an expression of calm; and, indeed, in none of the three figures is there any thought of suffering or pain. There is no suggestion of the trappings of death that is too often the prevailing idea with modern burial customs, and which figure all too frequently on the tombstones in our cemeteries. In fact, into this scene of farewell, of the fourth century before Christ, we can read a message of immortal life that is really Christian in spirit. The calm and peace which these figures show seem to prove their belief that in a better world they will meet again and renew their intimate relations, and that the parting is but temporary.

The woman wears a simple, yet extremely graceful, costume. Her undergarment, or chiton, is made with sleeves, which are formed by bringing the ends of the drapery together by a series of brooches. These sleeves, if, indeed, they can be so called, extend only to the elbow, leaving the forearm bare. Over this chiton a heavy wrap, called a himation, is thrown shawl-fashion over the shoulders and lies across her lap. Her feet, clad in sandals, rest on a footstool. Her hair is short and curly, done in a coiffure of rather studied simplicity.

The man whose hand she clasps, and who is in all probability her husband, stands before her. His face, though calm, shows deep feeling and affection, and there is a certain nobility about his entire aspect. He wears merely a himation, which falls over his left shoulder, leaving the right shoulder, the breast, and the right arm bare; below the breast this garment is draped around him, and reaches to his feet, He has thick, wavy hair, and a full beard.

In the background, between the two principal actors in this little scene, is another man, somewhat older in years, perhaps the husband’s father. He, too, has a full beard, thicker and heavier than that of the husband, and thick hair; but although his hair is of a much thicker growth, he is evidently older than the others. He, too, wears a himation only.

All three figures are carved in very high relief, the heads being almost in the round. This is a sign of relatively late date, perhaps the second half of the fourth century B.C. The preservation of the figures is remarkably good.

Before enlarging on the artistic excellence of the relief, it will be necessary to discuss the remaining peculiarities of this stele, both architectural and epigraphical. Let us, therefore, first examine what may be called its architecture. The figures are enclosed in a temple-like structure, as is almost always the case with these grave reliefs. At each end of the stele is an anta-column of the Doric order, perfectly plain, and topped with a simple capital. Resting on them is a lintel, or architrave, bearing an inscription. Above this is a molding, on which can be traced an egg and dart pattern. Then comes a plain cornice, surmounted by another similar molding. Above this comes the roof. And here we have a real peculiarity. Most of the stelae that have come down to us have a roof as seen from the front, with a tympanum; this, however, departs from the usual custom, and has the side view instead. Thus, we find that this stele is not only remarkable for its artistic excellence, but for certain archæological peculiarities. In this side view even cover tiles are inserted, the two at the end being represented as corner tiles. The central cover tile is surmounted at the ridge by a boss of marble, held in place by a seal of lead, in a hole that has been drilled for its reception. It seems likely that this may have been for the base of a palmette, or for some other ridge ornament; for such decoration was not unknown among the Greeks.

As has been said, there is an inscription running along the architrave. At first, the correct reading of the inscription, and the solution of the problem that is offered, were difficulties that seemed almost. insurmountable. In the first place, it is very lightly cut in the stone, and is almost illegible, so that I am not certain that the readings offered are altogether correct; in the second place, part of it is in one line only, part in two. Various methods were tried to read this inscription, which, as has been said above, was almost illegible. It was finally decided to make a plaster cast of the inscription in the hope that by this means all the letters would come out clearly. In this method the problem that was offered has been satisfactorily solved. There is really not one inscription on the lintel, but three; and these are the names and patronymics of the three persons represented in the relief. The name of the woman, as we find it on the inscription, seems to have been

ΚΡΙΝΥΙΑ ΑΣΤΡΑΤΙΟΥΘΥΓΑΤΝΡ

Κρινυία, Ἀστρατίου Θυγατήρ, meaning, “Krinuia, daughter of Astratios.”

The man in the center has, over his head, the following legend:

ΝΑΥΚΛΑΙΟΥΣ (?)

N . . . . . . . . . .

Nαυκλἢς Nαυκλαίoυς (?) N—(rest illegible), or “Naucles, the son of Nauklaies, N—.”

The woman’s husband bears the name

HAΥKΛAEIOΥΣ

NAΥ . . . EΥΣ (?)

Ναυκλαίης Ναυκλείους, Ναυ—ευς (?)

“Nauklaies the son of Naukles, Nau. . .eus(?).” This latter is probably the name of the “deme” or district in Attica, of which he was a citizen.

The faintness of this inscription makes the above readings subject to criticism, and I do not vouch for their absolute accuracy; but, in the main, I am satisfied with these interpretations. Some scholar may, in the future, take occasion to differ with me, and his readings may be better than mine. I should in that case be very glad.

A discussion of the technique and artistic value of this stele must be qualified by one very important statement. We must constantly bear in mind the fact that only under very exceptional circumstances were great sculptors employed to make these reliefs. We moderns do not, as a rule, employ our greatest sculptors for our tombstones; no more did the Greeks. They chose artisans and stone-cutters to make these monuments. Yet, so great was the technical skill of these workmen, and so universal the feeling for beauty among the Greeks, that these stelae, never by them considered works of art of importance, are to us not only sources of fruitful and profitable study for the archææologist and research-worker in classics, but objects of joy and delight for all who love beautiful things. The existence of such an object in Philadelphia will be a constant reminder that the people who produced it cannot without irreparable loss be thrown into the discard of education. The presence of this stele in the University Museum should be in itself a powerful incentive to the teaching of Greek and Latin in our schools.

S.B.L.