Museum Object Number: 30-51-1

Image Number: 3306

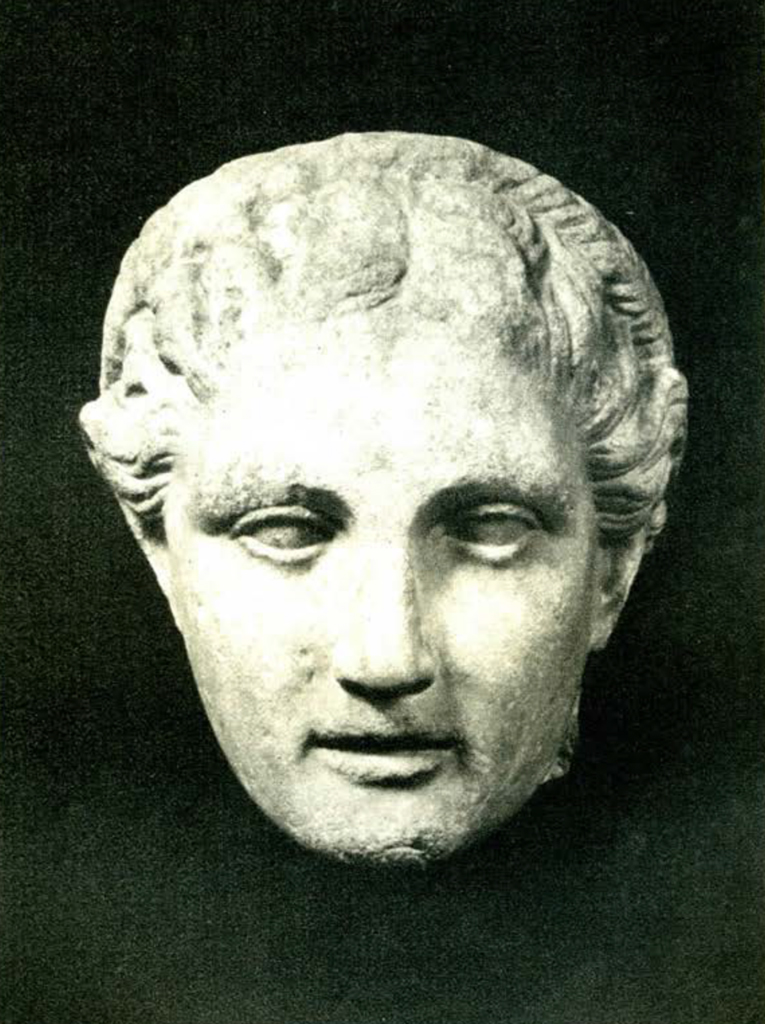

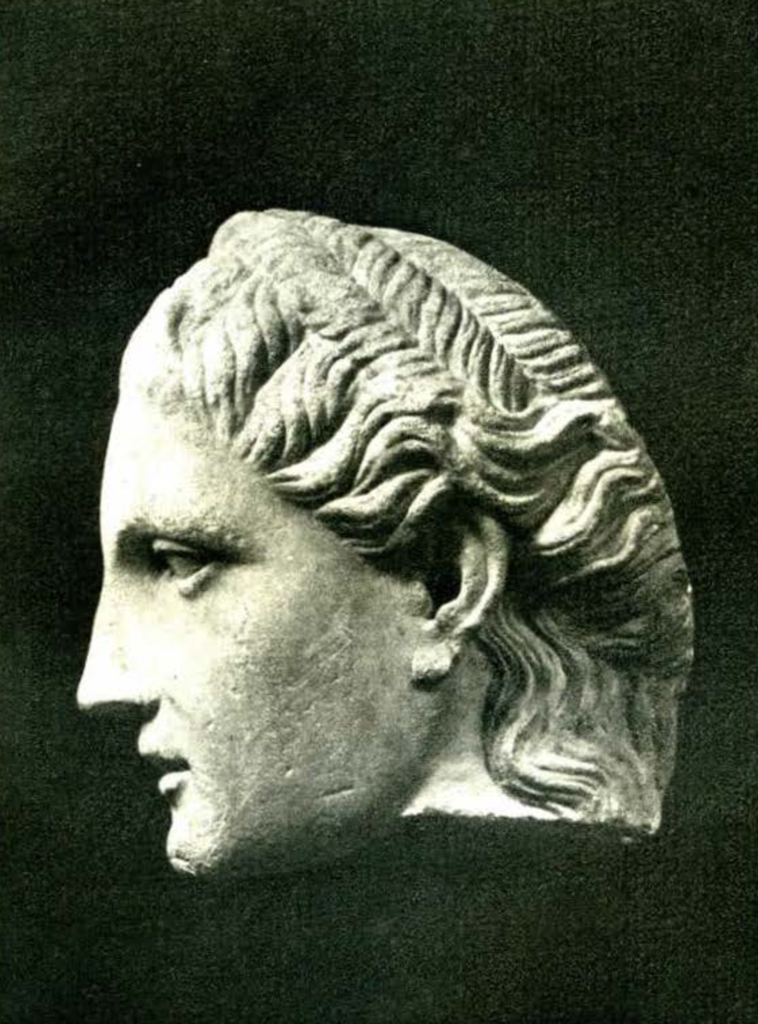

TWO Greek heads have recently been put on exhibition in the Pepper Gallery at the head of the main stairs. One, of heroic size, doubtless comes from the statue of a goddess, but in what sanctuary the statue stood or what goddess is represented is not now known. The head is reported to have come from the collection of marbles at Deepdene Park, Dorking, the country-seat of Thomas Hope, the well-known banker who made a fortune in Amsterdam in the closing years of the eighteenth century, and returned later to England with a collection of sculpture and vases which has enriched museums all over the world. The natural assumption is that the head was acquired by Hope himself, but on the other hand both the Arundels and the Howards were former owners of Deepdene, and were themselves collectors, so that it is quite possible that the head was already at Deepdene before the Hope collections were brought there. In 1917, just before the Hope marbles were sold at Christie’s and while the cataloguer was already working at Deepdene, he was told by a gardener on the place that other marbles lay buried in a sand-cave in the park. Since it was then too late to include these pieces in the sale at Christie’s, they were sold separately at a subsequent date. Among them, according to report, was this head.

The crown of the head, now missing, was made from a separate piece of marble, the joint having been concealed by the braids which encircle the head. For the reception of this piece, a deep hollow was worked in the head at the lowest point of which may be seen the hole for the dowel which bound the two blocks together. The neck is entirely missing.

The head is rendered in a free and entirely plastic style which suggests a date fairly late in the history of Greek sculpture. The elaborate arrangement of the hair confirms this view. Braids of hair wound about the head occur on coins of the fourth century before Christ, but they are more frequently met in the art of the succeeding century, to which our head may best be assigned.

Museum Object Number: 30-7-1

Image Number: 142154, 3312

Museum Object Number: 30-7-1

Image Number: 142155, 142156, 3192

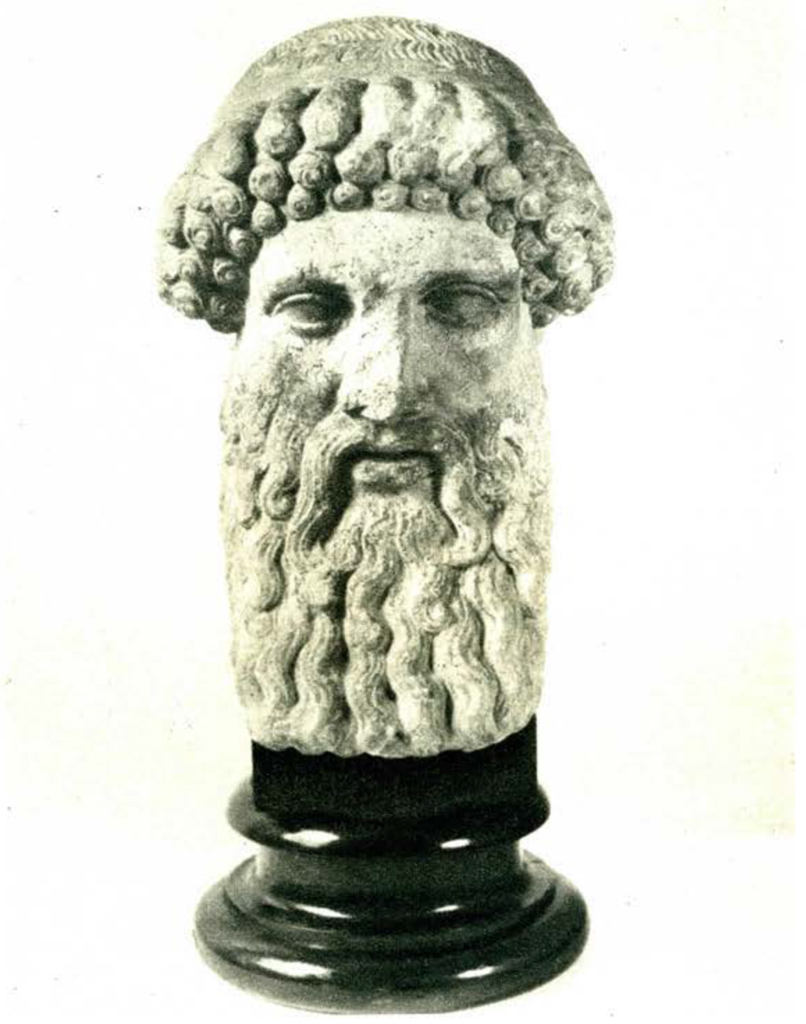

The other head was acquired last November at the sale of the Baron Heyl collection in Munich. It comes not from a statue but from a herm which is a semi-anthropomorphic image of a deity consisting of a square pillar surmounted by a human head. There were Dionysos-herms, and Hermes-herms and two-headed herms, but of these the Heremes-herms were the most numerous especially at Athens. To the historian they are familiar from the account in Thucydides of the shocking events which preceded the departure of the Sicilian expedition: ‘But in the mean-time the stone statues of Hermes in the city of Athens- they are the pillars of square construction which according to local custom stood in great numbers both in the doorways of private houses and in the sacred places- nearly all had their faces mutilated in the same night.’ To the student of sculpture they are familiar from a number of replicas, the most important of which was found in Pergamon in 1903 and was inscribed with the words; ‘You will see that this is Hermes, the work of Alcamenes.’

To the head of this herm our new acquisition is closely analogous; there are the same formal rows of tight curls above the forehead, the same square protruding beard and there were once the same long tresses on the shoulders. The identity of our head is therefore certain. Since the discovery of the Pergamene head, it has been usual to call all Hermes-herms of this general style replicas of the work of Alcamenes, but this is patently wrong; not only is it inherently improbable that all the extant herms should go back to one original, but differences in style may be detected among them. Most of them, in fact, are copies of a work considerably older than that of Alcamenes. Our head also is referable to an earlier prototype, although it is by no means a slavish copy but rather a fresh version of the subject, for it was made not in Roman times but in the fourth century before Christ. The deep-set eyes and the delicate modelling of the cheek suggest the heads on Greek grave-stones of this period. These features are in marked contrast to the archaic hair and heard which are purposely rendered according to the conventions of an older style, probably out of deference to the architectonic form of the herm and to its association with an older and more primitive form of worship.

E. H. D.