THE years which immediately followed the founding of the University Museum, the late nineties, witnessed ceaseless activity in the excavation of antiquities from Italian soil. The methods employed by the excavators of those days did not, however, conform to scientific standards; in spite of the untiring zeal of Italian scholars, who from the first realized the importance of pre-Roman antiquities, Italic and Etruscan vases and bronzes were constantly unearthed both by landed proprietors who sold the products of their soil to the highest bidder, and by illicit diggers who worked at night and kept no records of their plunder. By such ruthless spoliation the museums of Europe were steadily enriched.

Museum Object Number: MS1399 or MS2467

Image Number: 5071

In 1897, largely through the activities of Sara Yorke Stevenson, the University Museum decided to enter this rich if precarious field. With funds generously provided by John Wanamaker and Phoebe A. Hearst, Professor A. L. Frothingham of Princeton went to Italy as representative of the Museum to purchase Italic antiquities. The method adopted was to buy groups of objects from Italian excavators, and although Professor Frothingham was not himself present when the tombs from which these objects came were cleared, the men with whom he dealt were in large part scholars, and in many cases he obtained from them both plans of the tombs and lists of their contents, which are preserved to-day in the Museum. The collection has thus more scientific value than many ‘Etruscan’ collections formed during the same period. In one other respect also the record of the Museum is admirable: every piece was acquired with the consent of the Italian government.

In addition to the objects assembled by Professor Frothingham, the Museum purchased in 1897, at public sale in Philadelphia, the ‘Etruscan’ antiquities of Robert H. Coleman. From these two sources was gathered a collection which, for purposes of study, is unrivalled in America, and in Europe is surpassed in a few museums only. In the northeast room, on the second floor of the Museum [Plate II], is now exhibited a representative selection of this wealth.

A chronological account of the collection begins with a restored pot [Plate III, left] and a group of sherds – in the southeast corner of the room-which come from a box of fragments purchased by Professor Frothingham at Orvieto. They are typical specimens of the pottery made by the indigenous neolithic inhabitants of the Italian peninsula, who lived in caves and rude huts, roamed the forests of the sparsely settled country, and subsisted chiefly by hunting. This race apparently lived on in Italy to the time of the Etruscans and indeed contributed a by no means negligible element to the mixture of races from which the Romans were evolved. They invariably buried their dead.

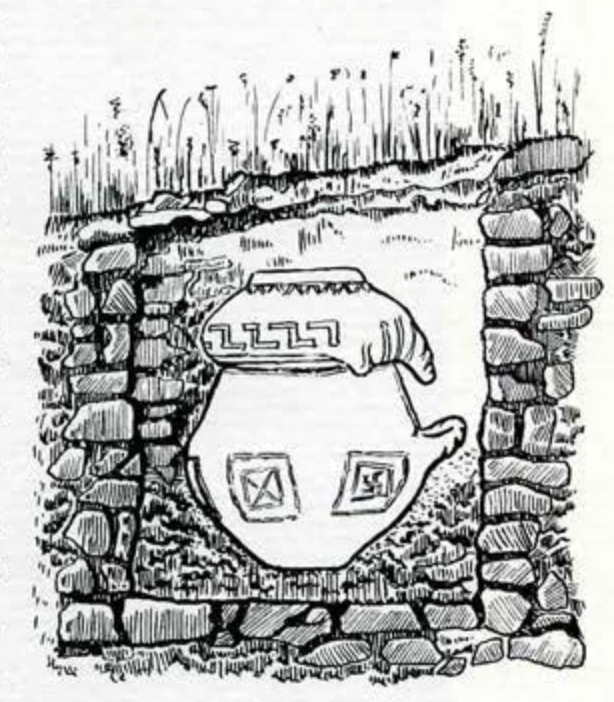

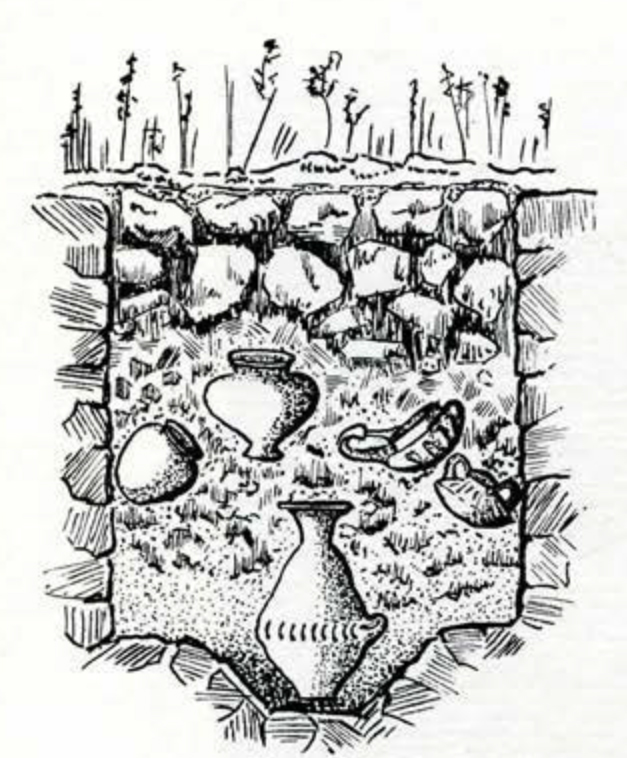

In the early bronze-age the Po Valley was penetrated by settlers from the north who cremated their dead. Whether they were a branch of the great Iudo-European race, whose migrations were convulsing Eastern Europe in this period, is not certain, but we know that they were an agricultural people, and though they had ceased to live in lake dwellings they still continued to erect their huts on piles. These are the terremare people, named from the Italian term, terra marna, which is used by the peasants of Parma to describe the mounds of black earth much prized for fertilizer, with which the villages of this early people are covered. No remains of these invaders are included in the collections of the Museum. But toward the end of the bronze-age, probably subsequent to the fall of Cretan power in the Mediterranean, the terremare folk had increased and spread southward over the Apennines into Tuscany and Latium. Their kinsmen or, according to some scholars, their descendants have frequently been called Villanovans after the village near Bologna where their cemeteries were first unearthed, but a more logical name, used in the Museum labels, is ‘Italic.’ Important among the remains left by this folk are burial urns [Plate III, center and right], in which the ashes of the dead were interred. They were generally covered and it is noteworthy that they invariably had but one handle, perhaps merely because a discarded pot, unattractive to thieves, was used for this purpose. In some settlements, especially in Latium, the burial jar took the form of a hut, that the dead might enjoy in the hereafter the comforts of the house in which he had lived. Examples of both types of urns are shown adjacent to the neolithic pot. In the earliest of these Italic burials [Figure A] only a few trinkets, those worn by the dead at the time of cremation, were interred with the cinerary urn, but as the wealth of the people increased, the offerings left with the dead increased likewise, and vases and bronzes were buried around the ash-urn in the well in which it was sunk [Figure B].

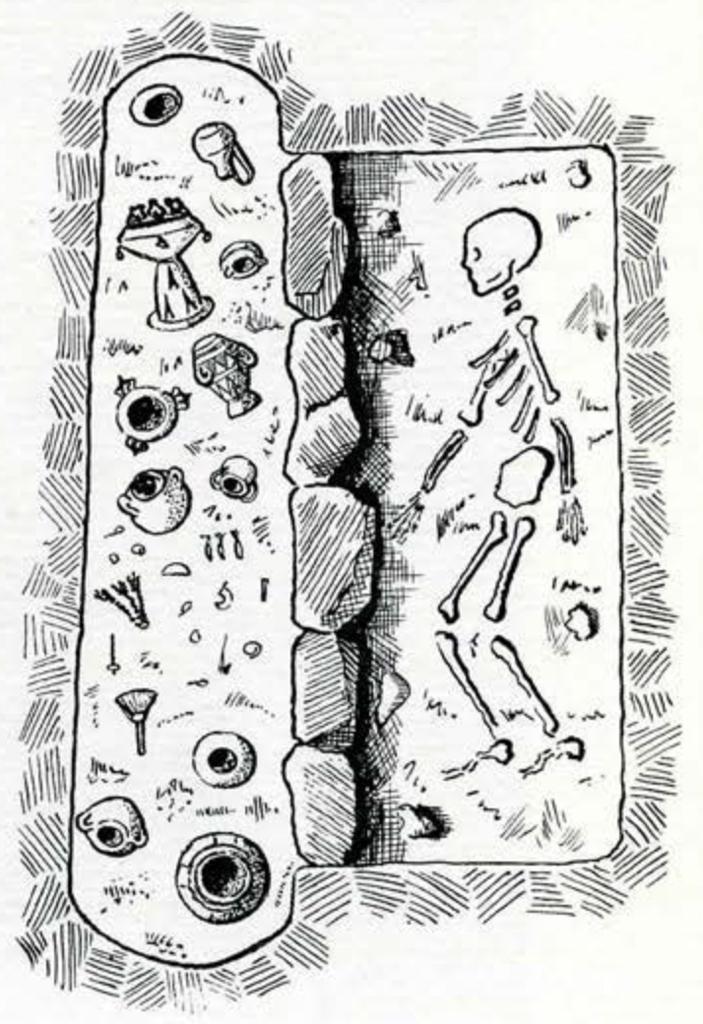

So far the story is simple, but in graves of the seventh century B. C. two innovations were made. First, a new type of burial makes its appearance [Figure C]. It is a trench instead of a well, and the reason is that the bodies are inhumed instead of cremated. Now the change from cremation to inhumation is not made lightly; it implies indeed a change of race, and yet, since there are jars in these tombs, sometimes empty and sometimes containing ashes, and since these jars are plainly derived from those which were used in well-tombs, the conclusion seems inevitable that by the end of the seventh century the northern invaders had intermarried with the primitive neolithic stock and that the burial rites of the two peoples survived side by side in these tombs. This juxtaposition of cremation and inhumation is clearly seen in the Faliscan territory, the Ager Faliscus, from which many of the Museum’s tomb-groups come.

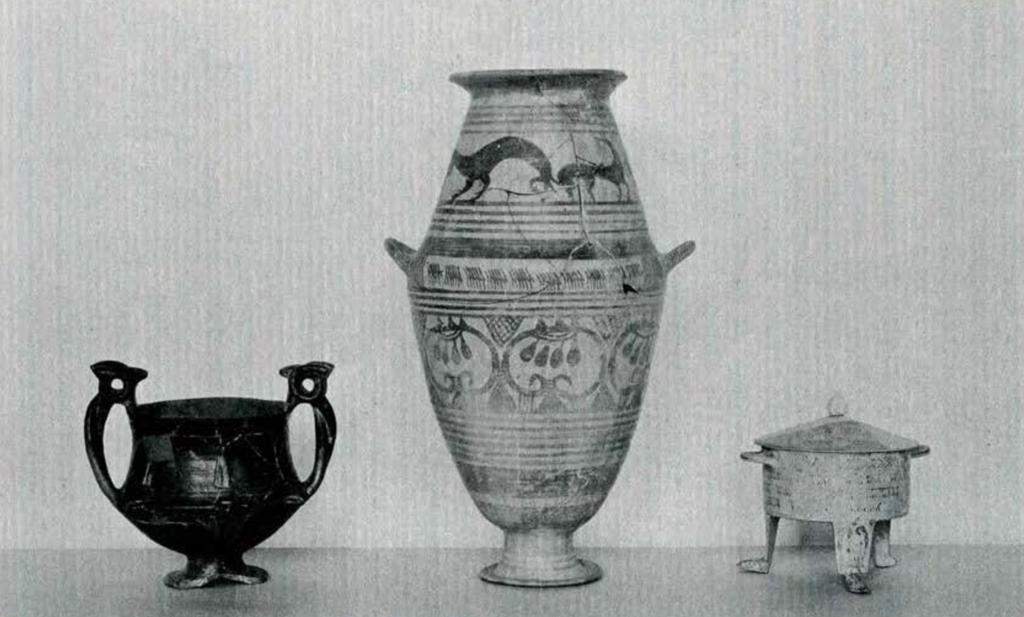

Image Number: 149994

The other new factor in the trench-tombs is the character of the offerings left with the dead. Gold is abundant, a mute witness to the growing wealth of the country, and the pottery is painted with designs which are plainly reminiscent of Greek geometric pottery, which implies extensive commerce. From a trench-tomb at Narce come the magnificent bronze helmet and breastplate [Plate IV] shown in the small case against the east wall. Both these pieces are deplorably corroded, but they are important both because they are ornamented with a wealth of geometric patterns, and because they are of unusual types. Several examples of helmets of this type are known, but the breastplate is unique. In a later trench-tomb, also from Narce, the contents of which are exhibited in the desk-case against the south wall, the style of decoration changes and the animal friezes are rendered with mannerisms generally attributed to oriental influence. Such animals appear on a cinerary urn [Plate VI, center], the shape of which, though derived from the primitive ash-urns, has undergone considerable changes. Precisely the same type of ornament as is found on this jar appears on a delicate pyxis [Plate VI, right], which might he regarded as an imported piece of genuine Protocorinthian ware were it not for this Italic type of decoration painted on the feet. The visitor to the Italic room who is concerned in studying the evidence for this great wave of oriental influence that swept over both the Greek and Italian peninsulas in the seventh century B. C. will be interested at this point to look at the amber figurines [Figure D] near the right end of the desk-case against the west wall. They were doubtless amulets, potent charms brought by traders from the East, and they show not only how religious ideas travelled (as to-day), westward from the Orient, but also suggest one way in which oriental types came to exert an influence on the art of the Italic peoples.

Museum Object Number: MS4882 / MS1601A / MS1601B / MS1600A / MS1600B

Image Number: 212097, 5103

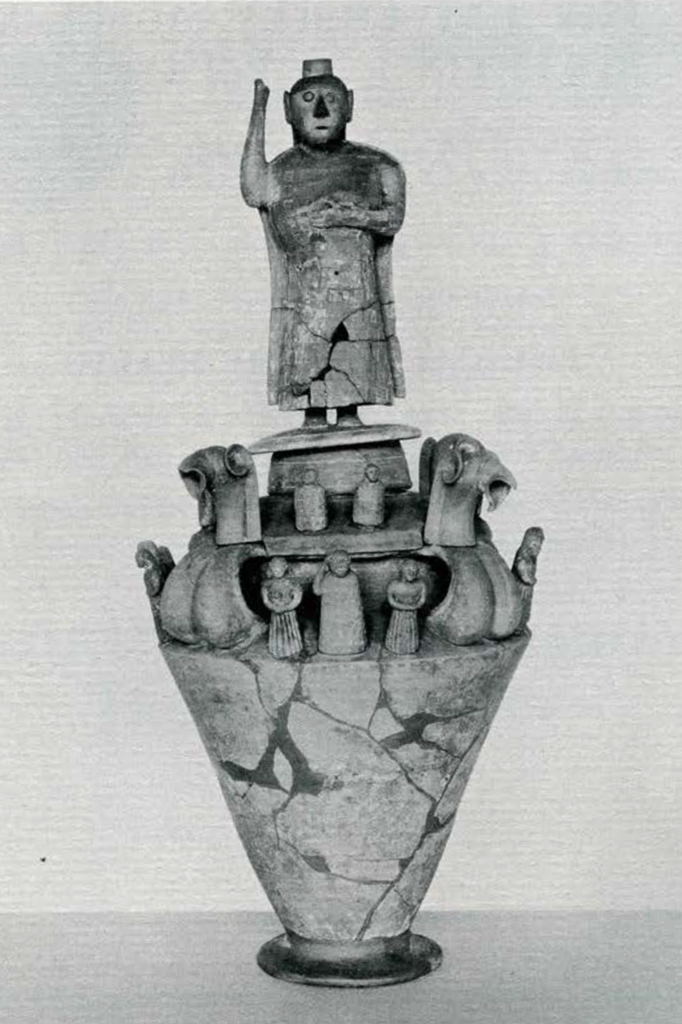

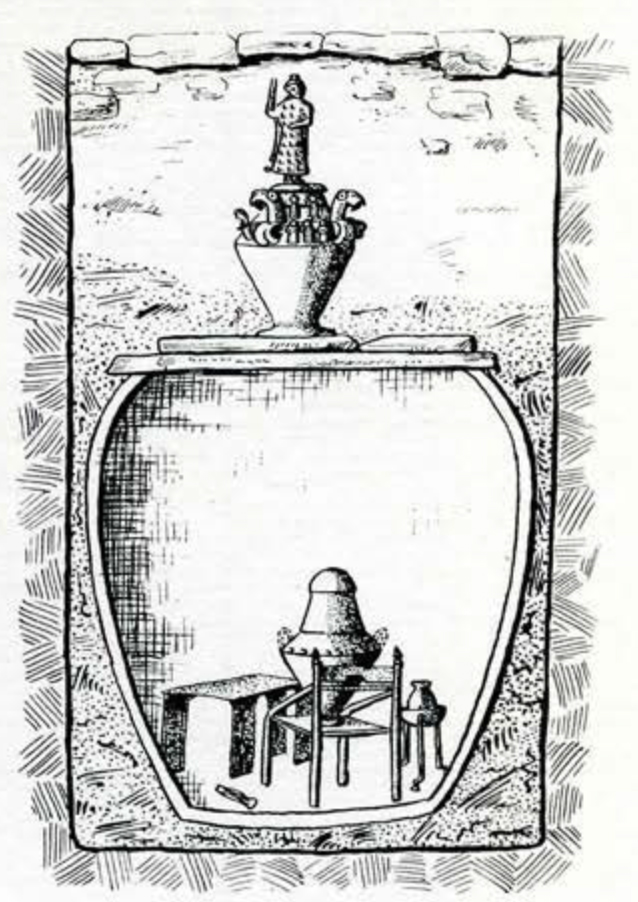

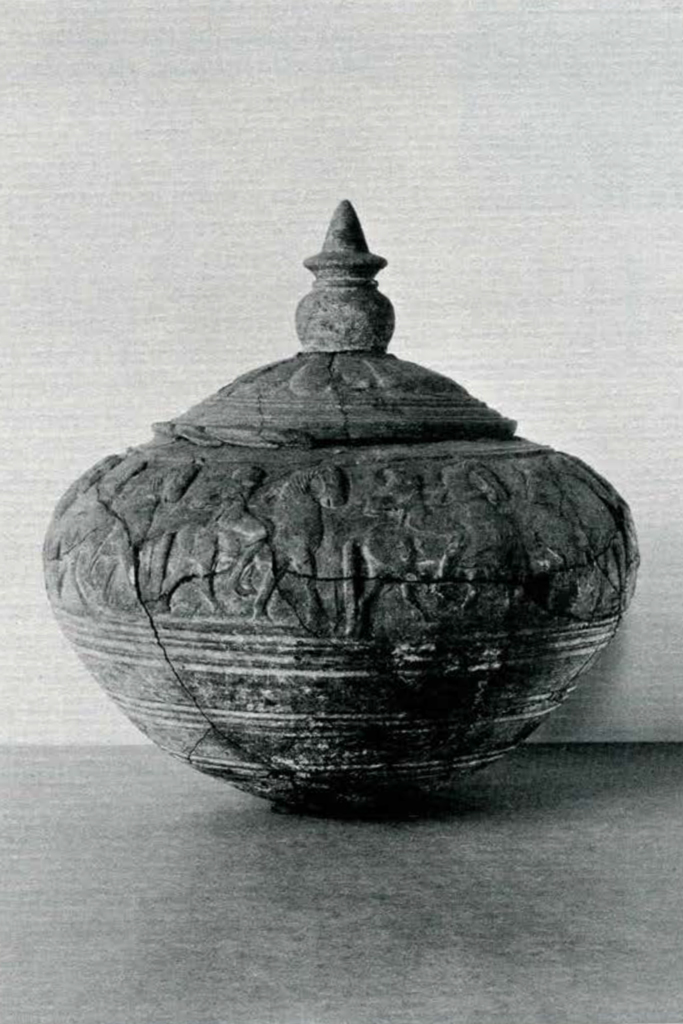

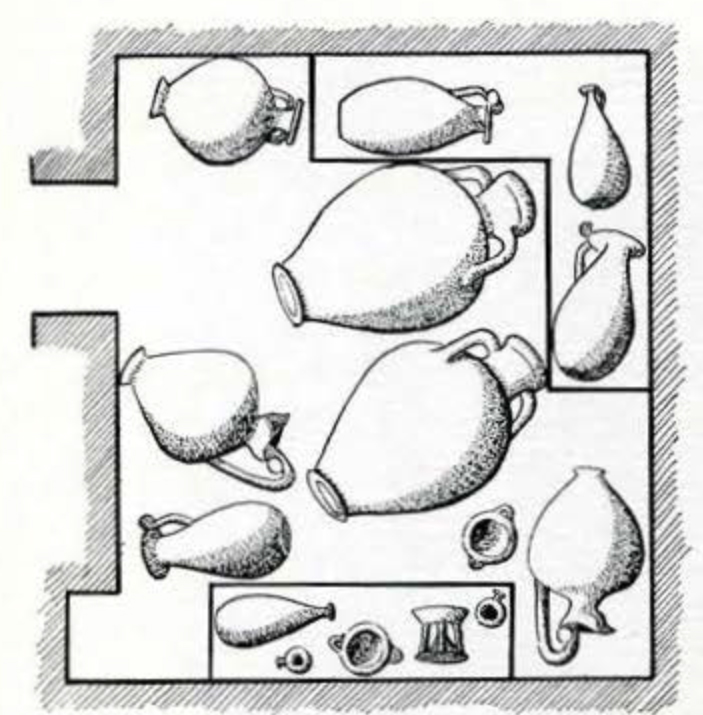

We have seen how the well-tombs were succeeded by the later trench-tombs. Another development is the ‘ziro’ burial. A ziro in the dialect of Tuscan peasants denotes a large jar, and a ziro burial is a well-tomb in which a large jar replaces small stones as a lining for the tomb. The Museum is fortunate in possessing most of the objects from a unique tomb-group [Figure E] of this less frequent type of burial, the only known example in which bronzes, shown in the northeast table-case [Plate V], were found together with the extraordinary type of vase ornamented with figurines, shown against the north wall [Plate I]. The story of the acquisition and identification of this tomb-group is not without interest. It was excavated in 1881 in Chiusi and reported briefly in the Notizie degli scavi of that year. Six months later an Italian scholar, Fiorelli, stated that the contents of this tomb had unfortunately been sold out of the country and had been acquired by the Boston Museum. No objects, however, to correspond with those listed in the Notizie are to be found in Boston. The statement of Fiorelli was repeated as late as 1925 by Bandinelli, and in 1924 Mr. Randall MacIver pointed out that one bronze vase from this tomb was in the Museo Archeologico in Florence, but that the rest of the contents of the tomb were sold out of the country. The history of the objects taken from this tomb is not, however, hard to trace. The catalogue of the Coleman sale, to which reference has been made, lists a vase ornamented with figurines like that of Plate I, and just those bronzes which were mentioned in the Notizie, namely a chair, a table, and a tripod. Now it is known that Robert Coleman bought his ‘Etruscan’ collection from James Jackson Jarvis, long a resident of Italy, so that when we read in his Italian Rambles that he was near Chiusi shortly after 1881, and note that the objects acquired by him tally exactly with those listed in the Notizie, there can be no reasonable doubt that the Museum possesses the contents of this now famous tomb.

The arrangement of this burial is shown in Figure E. The cremated remains were found within the bronze urn now in the Museo Archeologico. This urn had been set on the bronze chair and then placed within the jar. Next to it was placed a table on which was doubtless set meat and drink, and hard by the bronze tripod and bowl. There was also an axe-head, but this object has disappeared. After the ziro had been covered with slabs, there was set above it the extraordinary clay vase ornamented with figurines [Plate I] and the whole interment was covered over.

Since the body in this grave was cremated, it is natural to suppose that the dead belonged to the Italic race. But there is a new element here to be accounted for, namely a feeling for the personality of the dead. Over the chair had been spread a piece of linen cloth, clear traces of which are visible to-day, suggesting the Roman practice of sellisternium, the covering of a chair as a token of honor and respect. The table had also been covered with linen. Moreover, in other ziro burials, on chairs which correspond closely to ours, have been found bronze ash-urns with covers in the form of human heads not unlike in style to the heads of the figurines of the large vase set above our ziro. This feeling for personality is, in the opinion of some scholars, to be associated with a new race which now makes its appearance on the Italian scene, the most baffling as well as the most interesting of the pre-Roman races of Italy, the Etruscans. But the Etruscans did not cremate their dead, so that we are again driven to a compromise and to the view that there must have been intermarriage between the rich Etruscan merchants who arrived from the East by sea, and the earlier stock.

There are, all told, less than half a dozen examples extant of the large clay vases ornamented with figurines, which were set above ziro burials. Our Museum, then, is unusually fortunate in possessing two of them, the second of which was purchased by Professor Frothingham, and was reported to come also from Chiusi. It stands beside its sister piece from the Coleman Collection.

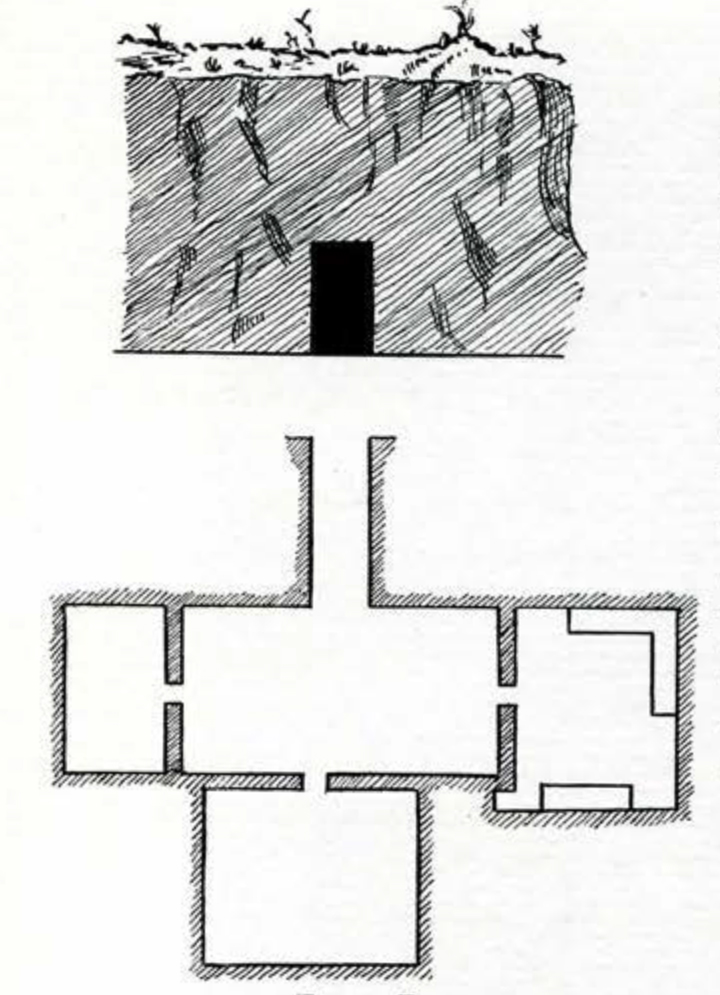

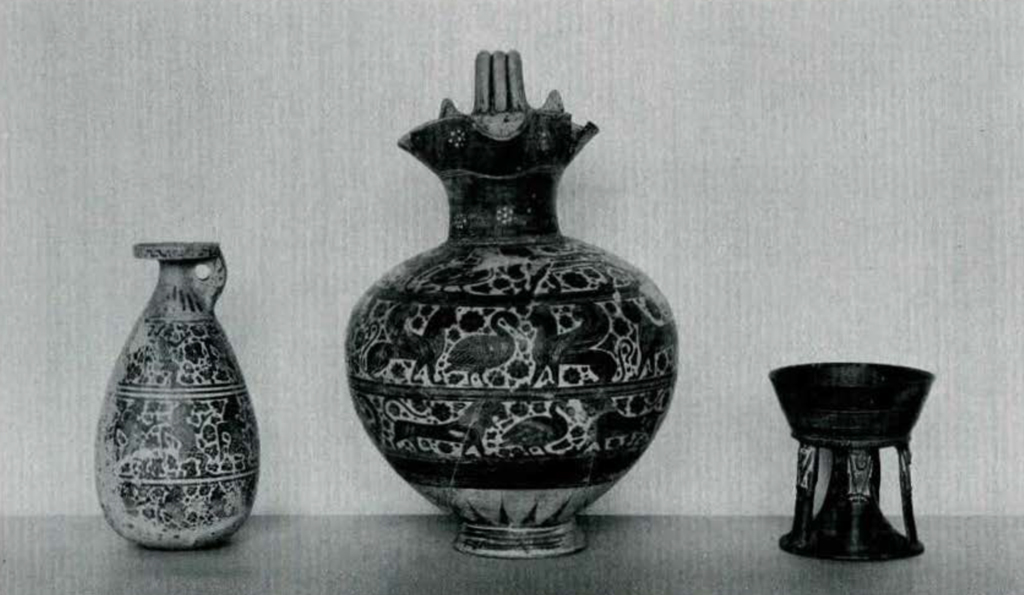

Before the ziro burials had gone out of use, in the first half of the seventh century, there came into fashion another type of tomb, built in the form of a chamber [Figures F and G]. The contents of such a tomb excavated at Vulci are shown at the end of the desk-case against the south wall, on the upper tier. The plan of the tomb showing the position of the objects found was made by the Italian scholar Mancinelli, who conducted the excavation. The unburned bones of the dead were found beneath the benches on which the vases were set, in a side room. We have here, then, a type of tomb similar to the famous painted tombs of Etruria, and typically Etruscan. Two of the finest Corinthian vases from this tomb are on display in the Sharpe Gallery. Other pots [Plate VII, left and center], of native Corinthian ware are exhibited here, and beside them Etruscan imitations, for the Etruscans not only carried on brisk trade with the cities of Greece, but also were facile imitators of the products which they imported. Sometimes the difference between the real Corinthian pieces and the clever Etruscan imitations of them is hard to detect, but in this case the absurd drawing of animals and the dead dull finish of the pot give away the hand of the inferior craftsman. There were also found in this tomb the two large storage jars which stand in the middle of the room. They are noteworthy, first, because precisely similar jars are in the Louvre and, second, because on either of them just below the rim are scratched three Etruscan letters. These are probably the earliest of any of the Etruscan inscriptions shown in this room, the Corinthian vases from this tomb fixing the date as close to 600 B. C. If the visitor to the Italic room will leave the Vulci tomb-group for a moment and inspect the other examples of Etruscan writing in the room – on two unpainted jars in the southeast corner, on the two cinerary chests, on a bucchero sherd in the northwest table-case, on a strip of silver in the west desk-case, and on the bottom of a black figured vase in the same case-it will be seen that the alphabet of these inscriptions (which are invariably written retrograde) is Greek, but that the language is non-Greek, just as in later times the Russians borrowed Greek letters to write a language entirely distinct from Greek. Most of these inscriptions are known to European scholars and appear in the Corpus of Etruscan Inscriptions; on such epigraphical material is partly based the theory that the Etruscans came from the East.

Museum Object Numbers: MS2536 / MS2538 / MS2537 / MS2535

Image Number: 3641

To return to the Vulci chamber-tomb: beside the Corinthian and pseudo-Corinthian vases in this tomb was a single piece, a stemmed chalice [Plate VII, 3], of a typically Etruscan smoke-blackened ware called bucchero. It is a late example of the early phase of bucchero ware which is thought to end in 600 B. C., and thus confirms the evidence afforded by the Corinthian amphora for dating the tomb.

An example of the middle phase of Etruscan bucchero is the amphora set on a pedestal near the west door. The decoration is now frequently applied with a stamp, and it is amusing to note that in this piece the decorator has made a mistake and applied the figures of one frieze upside down. In the northwest table-case are shown examples of a third phase of bucchero ware in which the decoration is moulded; to this period, the third quarter of the sixth century, belong the large brazier in the center of this case and the fine covered bowl [Plate VIII] with a frieze of horsemen in relief.

Figure E.

Image Number: 5065

The versatility of Etruscan potters is shown by the variety of reproductions of foreign wares which they turned out; a number of these are shown in the desk-case against the west wall, and the latest in date stands on a pedestal in the northwest corner, an imitation of a red-figured Attic vase of 490-470 B. C. [Plate IX], on which is depicted a scene entirely in accord with Etruscan taste, the murder of Aegistheus by Clytaemnestra. This vase was published in Italy in 1853 but has been lost for years, until it finally was discovered in the collection of Miss A. M. Hegeman, of Washington, who has generously loaned it to our Museum.

The Etruscans were a people famous for their powers of divination. In the table-case at the east end of the room are two bronze carts, both of them partly restored, containing bronze vessels. With one of these carts were found a candelabrum, a flesh-hook, andirons, spits and other ritual apparatus which might have served in a religious sacrifice and the subsequent prognostication based on the appearance of the victim’s vitals. In the bronze vases of the cart which was found with these implements are preserved the wooden stoppers which closed them as if they once contained precious oils or wines used in the sacrifice. We have called the objects Etruscan, but no sooner is the attribution made than doubts arise. The bronze vessels in the other cart suggest, with the exception of their vertical handles, the type of amphora found in Faliscan burials. Can it be that even in the religious rites of the Etruscans early Italic elements were incorporated?

Museum Object Numbers: MS2730 / MS2732A / MS2732B

Image Number: 3717, 212068

Museum Object Numbers: MS548

Image Number: 4052

In tracing the history of Italic and Etruscan sculpture, the story is the same: there are examples of an early Italic art, of a quickening influence from the East, and of an Etruscan art that came under strong Greek influence. The early examples of Italic art are on a small scale, but the artist who could model the humorous figurine of a pygmy on an ass’s back (shown in the desk-case against the south wall) was no novice. The crude and ugly figures which surmounted the vases set above ziro burials may be also counted as Italic, although as we have seen, Etruscan influence may at that period have begun to make itself felt. A much more spirited piece of Italic workmanship is the bronze statuette of an armed warrior [Plate X] exhibited in the southwest table-case. It gives a very good impression in parvo of what the terra-cotta statues of the seventh century must have been.

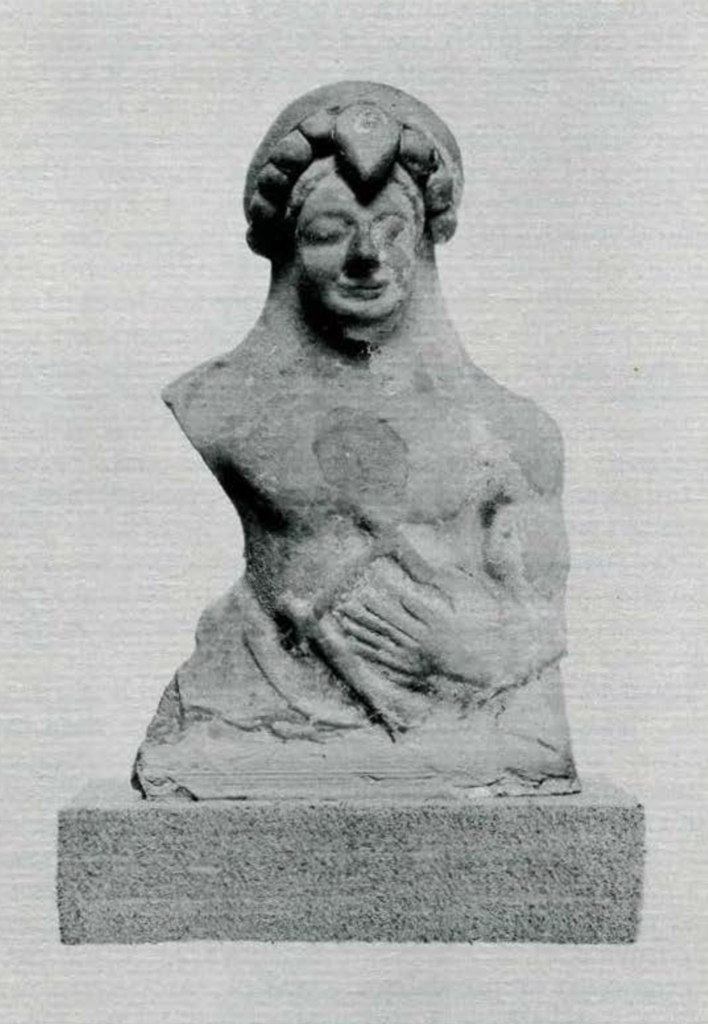

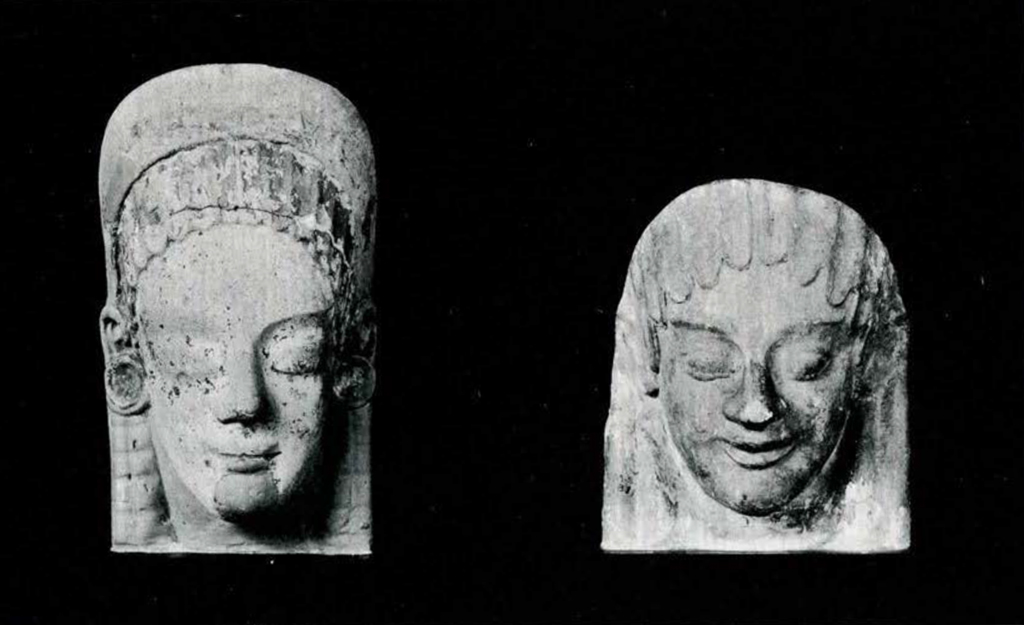

One of the most interesting pieces of the sculpture in the collection is the head of Plate XII, which has never before been exhibited, but is ow shown at the right of the west door. It is made of a coarse stone, pietra fetida, so ill adapted for sculpture that it is no wonder that the inhabitants of the Italian peninsula preferred to model in clay rather than to attack a stone at once so coarse and so hard. The chief interest of the head is that it is of the type loosely termed ‘Dædalid’ after Dædalus of Crete, who is credited with having taught sculpture to the Greeks. Very few heads of ‘Dædalid’ type have been found in Italy. This head, moreover, can be dated by the pottery found with it, now shown in the adjacent case, to a period not far from 600 B. C. The long tresses of hair, the low forehead, the high-rounded cheeks are all characteristic of the ‘Dædalid’ school, but it is highly improbable that this piece was derived from a Cretan prototype, for the arrangement of the strands of hair suggests Cappadocian or Lydian art of the late seventh century.

Museum Object Number: 48-30-2

Image Number: 3116

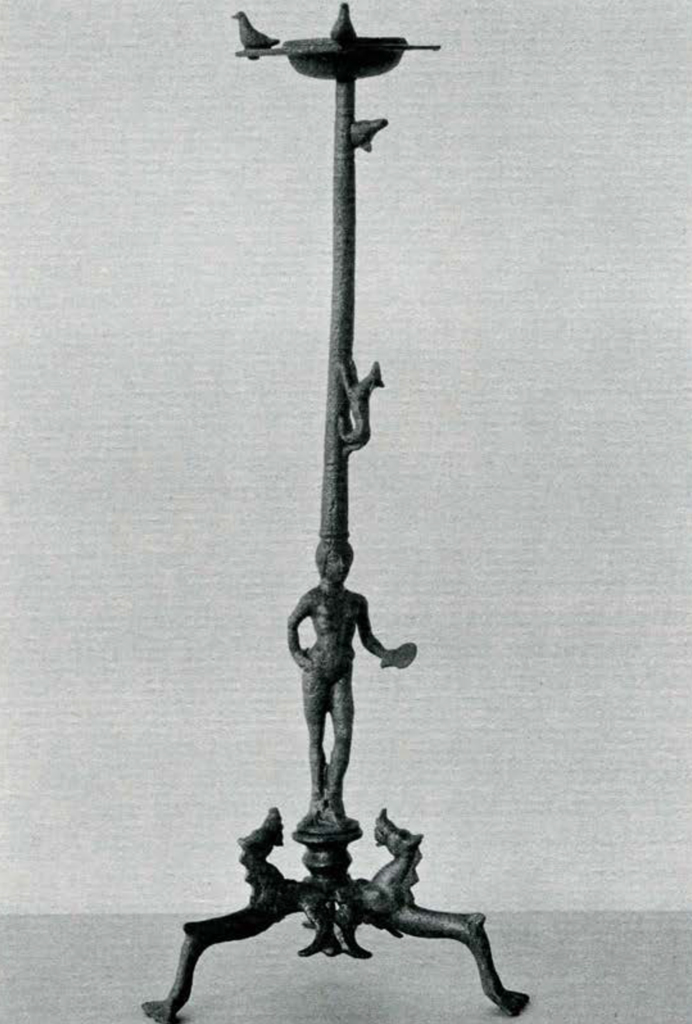

The fragmentary figurine of Plate XIII, together with other similar figurines exhibited on the shelf to the right of the ‘Dædalid’ head, probably comes from Tarentum, and like other terra-cottas from this site they were offerings made at graves in honor of the dead. They represent banqueters, and refer, of course, to the funeral banquet. In date they are a century later than the ‘ Dædalid’ head and in style they betray strong Greek influence. A bronze statuette which shows Greek influence at its height [Figure H] is shown in the southwest table-case. It represents a striding youth with one arm upraised, and is hardly distinguishable from a Greek piece. In the same case with this statuette is a dipper, the handle of which terminates in a charming piece of modelling, a snake with a dove in its mouth. The more decadent taste of the fourth century is shown by the candelabrum [Plate XI] shown at the end of the west desk-case. The main support is in the form of a nude girl, mirror in hand; from her head rises a rod which supports a basin on which doves are perched. Up the supporting rod a cat is chasing a dove. Terra-cotta sculpture of the late third century is represented by the head on a pedestal in the northwest corner of the room. From approximately the same period are the two cinerary chests in the south corners on which are rendered in relief two tragic scenes which, it would seem, appealed to Etruscan taste: on the one, the death of Priam; on the other, the fratricidal combat of Eteocles and Polynices.

In painted architectural terra-cottas the Museum is exceptionally rich. The lavish use of such ornaments on Etruscan temples, which persisted until the second century B. C., is attested by many passages in Roman writers. Cato the Censor rebuked his fellow-citizens for laughing at the old-fashioned ornaments of their temples and for preferring Greek art; the Elder Pliny in his Natural History expressed similar views; but Vitruvius, whose architectural treatise dates from the time of Augustus, called the Etruscan temples which were loaded with such ornaments, bary-cephalæ or top-heavy. The Etruscan temple was built of sun-dried bricks and wood. The roof was a low, broad gable-roof extending far over the sides so as to protect the brick walls against rain. At the corners were placed acroteria; along the long sides, set against cover-tiles, the antefixes; and at the ends of beams, to cover unsightly wooden construction, revetments. The moulds for making these fictile ornaments were probably carried from one building operation to another by the architects. The deity to whom the temple was dedicated was represented by a cult statue in the interior of the temple, but on the antefixes and acroteria were represented the dæmons, satyrs, and warlike maidens who followed in the deity’s train.

The antefixes are shown against the north and south walls of the room. The earliest [Plate XIV], from Cære, date from the sixth century, and recall the ‘maidens’ found in ther Persian debris on the Acropolis at Athens. They show a consistent development from the early to the ripe archaic style in the middle of the fifth century. The great shell antefixes [Plate XV], also from Cære, belong to a series, other examples of which are found in the museums of London, Berlin and New York, and date from the fourth century B. C.

Museum Object Number: MS2640

Image Number: 3596

Museum Object Number: MS1761

Image Number: 5086

The fragments of terra-cotta grills are exhibited on the west wall against restorations in watercolor made by Dr. Leicester B. Holland. They show a wealth of design and color and date from the same centuries, 600-200 B. C., as do the antefixes. The exact place on the temple to which these grills should be assigned is a matter of dispute. Dr. Holland believes that they were erected along the ridge-pole of the roof, but according to another view, which has gained some support from the Museum’s excavations at Minturnae, they stood along the raking cornice of the temple.

Museum Object Number: MS721

Museum Object Number: MS1933

Image Number: 3496

Museum Object Numbers: MS1813 / MS1811

Image Number: 3377 , 3379

Image Number: 3369, 3372