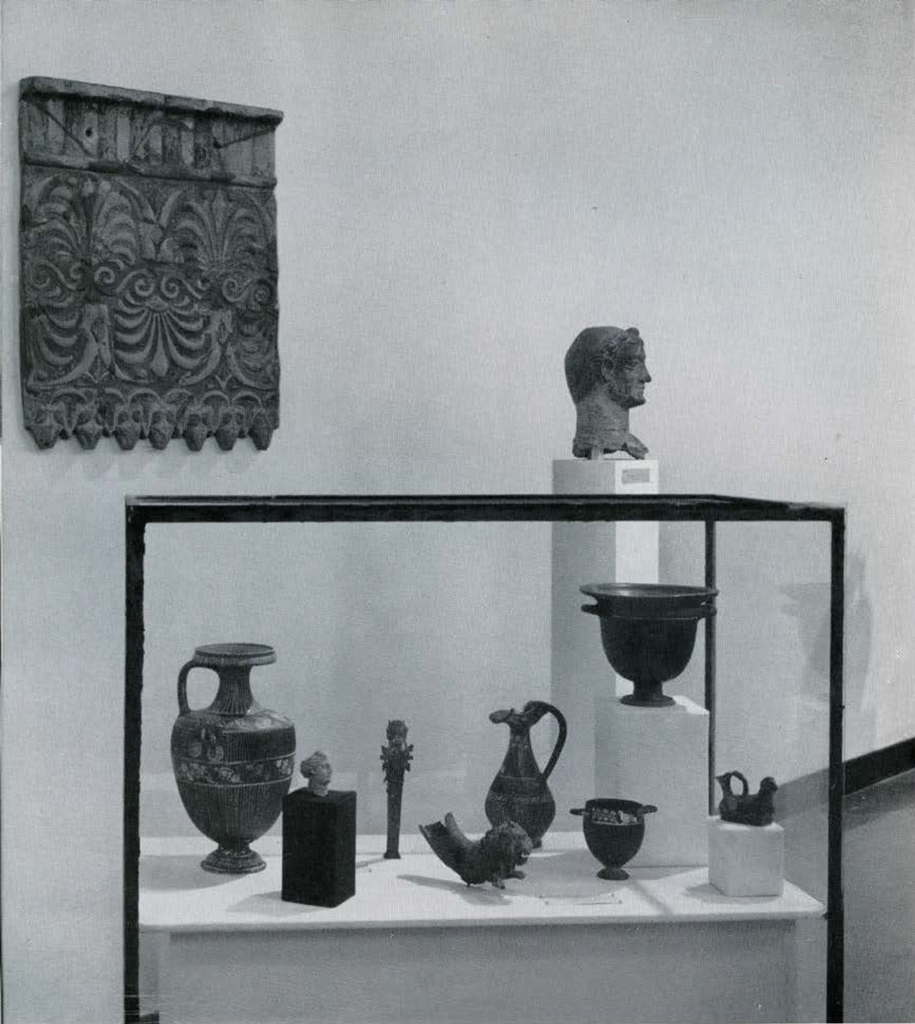

The most recent in a long series of remodelled galleries of the Museum were completed in April of this year. At this time two rooms devoted to the civilizations of ancient Italy and to the Roman Empire were opened to the public. Almost every year since 1949 some section of the Museum has been rearranged and redisplayed, and now in 1958 hardly a member of the Museum’s staff has not had some part in offering a solution to the always interesting, ever new questions of how to show and why we show our archaeological collections, and of whom are we really thinking when we show them as we do. It seems safe to say that no curator has ever believed for long that he has achieved a satisfactory answer to any of these questions in exhibits with which he has been involved. The final crystallization of ideas in the completion of an exhibit must always bring into focus still others which seem more desirable. The planning of exhibitions will always be a growing and enlivening process, and the opening of a new exhibit should realistically be regarded only as a step: forward, it is hoped.

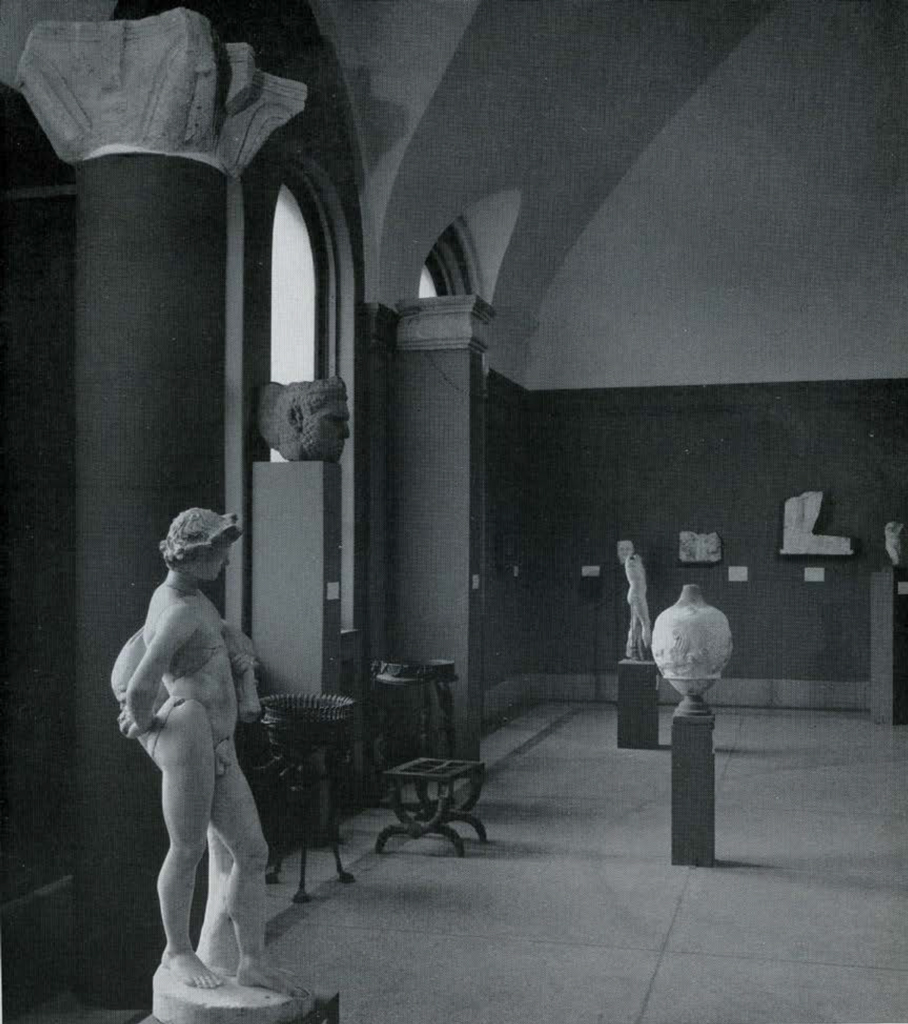

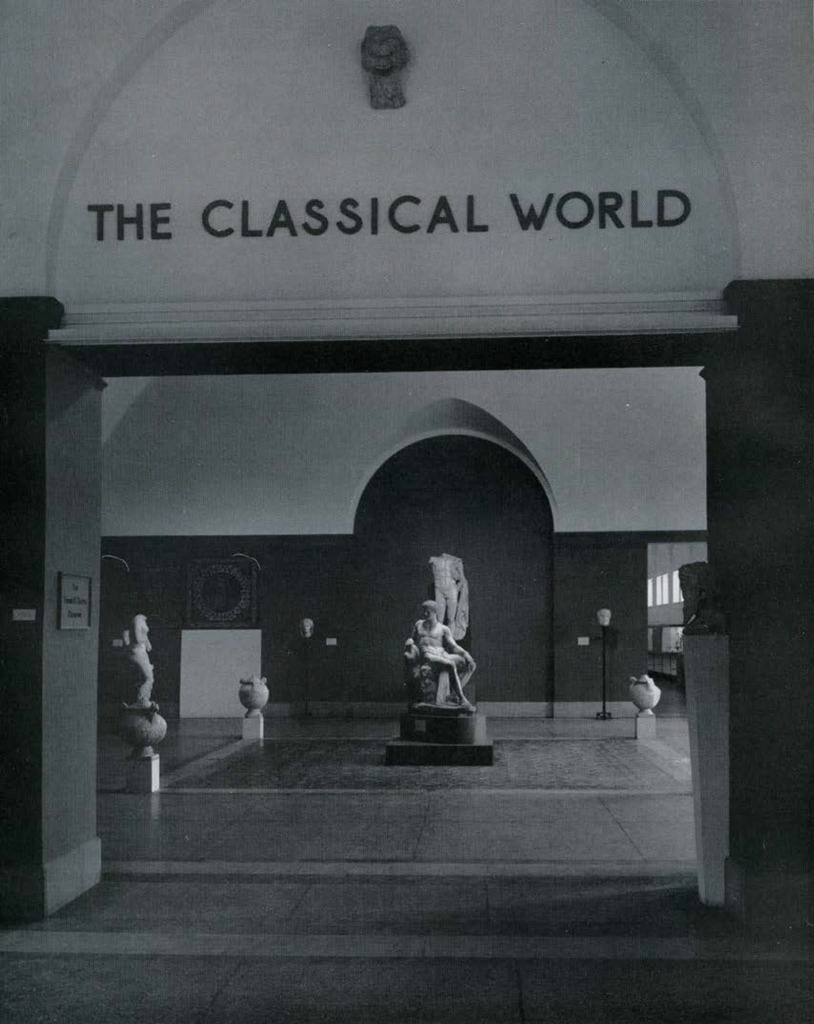

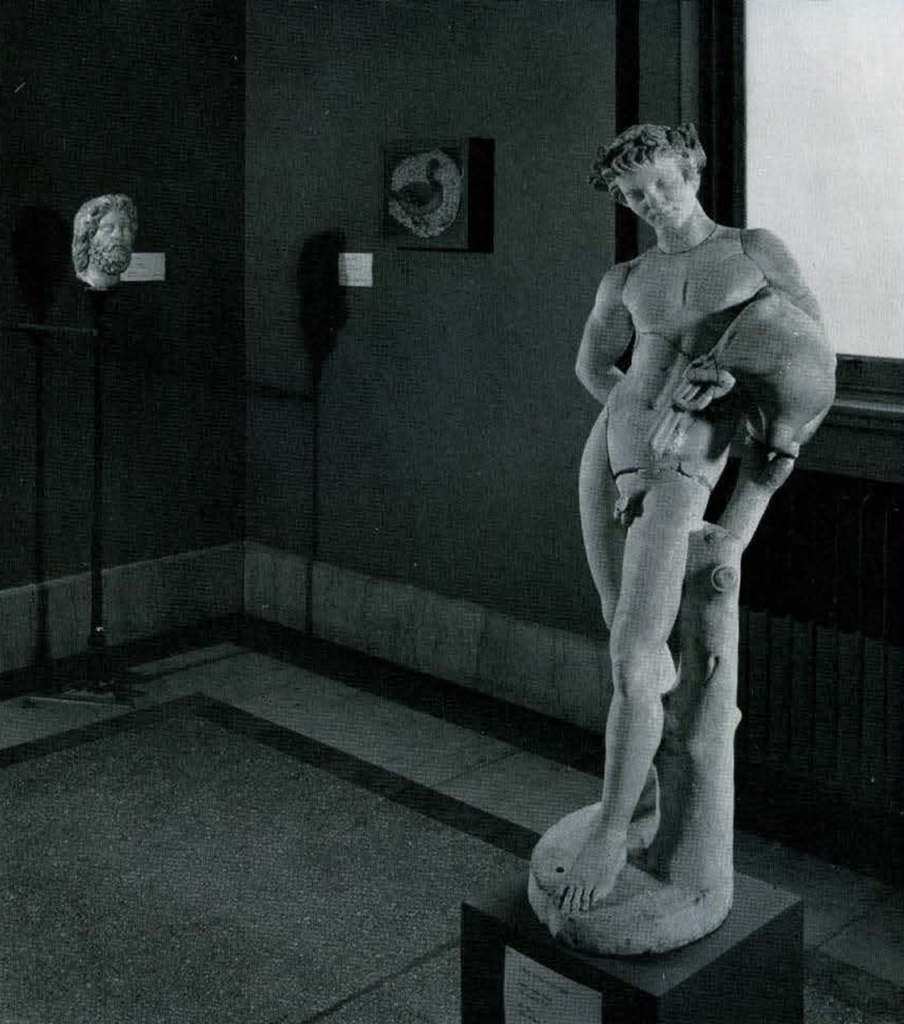

In the course of planning for the new displays an additional gallery was given over to the Mediterranean Section which in itself adds much to the possibilities for exhibition. The Edwin H. Fitler Pavilion, in which formerly the collection of musical instruments was displayed, now serves as a kind of introductory outer court for the Mediterranean collections. Here two intentions have been achieved. One was the provision of an attractive and, it is hoped, somewhat compelling view from a distance, suggesting the nature of the collections to be seen in this wing. The other was, in the display of sculpture and other pieces from all parts of the Roman Empire here, to give the visitor as his first contact with the Mediterranean galleries objects which can be expected to be reasonably familiar to him, leaving the less familiar to be reached by gradual stages of gallery progress. In this outer gallery the areas from which the pieces derive provide the geographical scope of all the Mediterranean collections. With regard to the quality of some of the pieces displayed, the selection of which was dictated in some cases by reasons other than their artistic merits, one might prefer to distract the visitor’s attention from the appearance of a particular object toward the general effect. The fairly frequent presence of numbers of art students in the gallery closely scrutinizing the sculptures as they draw from them suggests that we would do well to direct our attention to the acquisition of sculpture of higher quality in the future. But since taste and artistic discernment may be acquired through comparison and contrast, perhaps, after all, some public service is performed in the exhibition of pieces which are not out of the very top drawer. In the recent travelling exhibit of the artistic work of Picasso much that was poor was displayed along with the good. The former did much toward pointing up the very great qualities of the latter.

Museum Object Numbers: MS3452 / 39-42-1 / MS4013

Image Number: 62720

If one were to set out to try to define the main purpose of the University Museum in its field work and in its museum displays one might say that it is interested in the study of historic and prehistoric man, civilized and uncivilized, and ultimately in man’s origins; and in its displays it would like to give visual presentations of the various civilizations which man has developed, pointing up the important achievements of each, emphasizing the significant contributions of each to human civilization in general and in particular to our own. This, of course, is a very large order, especially in the case of fairly recent, highly complex civilizations, and if in the present displays the ideal presentation from the University Museum’s point of view has not been achieved it is humanly understandable. Let it be said that in the course of time it is to be hoped that we can show the Mediterranean collections in a more effective fashion from the point of view of the civilizations they represent. The addition of the new outer gallery makes more of a physical unit of the collections, and in the emphasis now given the section in the building plan, something of the basic significance of the contributions of Greece and Rome to our own civilization comes across, balancing well the equally, if not more, humanly significant Near Eastern collections in the opposite wing of the building.

In the detailed presentation of the collections much remains to be done if we wish to try to suggest to the enquiring layman through display what the significant achievements of his ancestral civilizations in Greece and Rome were and how they may relate to him. The problems of how best we might do this with the collections we now have and what supplementary pieces we might need for the purpose remain as interesting subjects for exploration in future displays and in future acquisition. So far, no museum has attempted a presentation of this sort with its Classical collections.

For the present, the new displays will suggest in part the character of the civilizations they represent in Italy and in the world of the Roman Empire, as some of the pictures of the new galleries here show. That they now appear in attractive settings with something of the glow of remote antiquity and the aura of the original thought and achievement of their civilizations about them is due to the devoted attention and high imagination of our manager of exhibitions, Mr. David Crownover.

Museum Object Number: MS851 / MS1601A / MS1601B / MS1606 / MS2728 / MS850 / MS2730

Museum Object Numbers: MS1369 / MS2251 / MS1363 / MS1360A / MS1360B / MS1358 / MS1359 / MS1355 / MS1356 / MS1362A / MS1362B / MS1361A / MS1361B / MS1357 / MS2503

Museum Object Numbers: 48-30-2

Museum Object Numbers: 34-23-1 / 48-2-271 / 48-2-291

Museum Object Numbers: MS4012 / MS24588A / MS2458B

Image Number: 149843