THE collections on display are distributed in three galleries: Upper Pepper Hall at the top of the main staircase; Harrison Hall-the great Rotunda of the Museum-on axis with the Main Entrance, and a small gallery connecting these two.

Museum Object Number: C657

Image Number: 1343

Museum Object Number: C656

Upper Pepper Hall is devoted principally to the exhibition of objects pertaining to the later periods of Chinese art, particularly those of the Ming and Ch’ing Dynasties. The Museum is not in a position to show all of these at once, and is compelled, therefore, to vary this exhibit from time to time. Permanently installed is the large brocaded palace velvet above the Main Entrance. Dating from the reign of the Emperor Ch’ien Lung (1736-1795) it is notable for its great size (length 26 feet) and for the beauty of its design of phoenixes and flowers woven with great technical proficiency in gold, silver and coloured threads brocaded on a rich black velvet background.

The crystal sphere usually shown in a vitrine in the center of the Hall is an extraordinary tour de force of crystal turning. It is the second largest example known, measures ten inches in diameter and was probably made in the latter half of the nineteenth century. It is said to have once been in the collection of the late Empress Dowager, and was presented to the Museum by Eldridge R. Johnson in 1927. The George Byron Gordon Memorial Collection supplements the sphere and was also presented by Mr. Johnson: it includes intricately carved table-screens of translucent jade and lapis lazuli, and coral and jade figurines of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. All of these illustrate the perfection attained by Chinese artisans in the working of hard stones.

Museum Object Number: C445

Image Number: 1335

When porcelains are shown in this Hall they are confined to the blue and white or the three-color porcelains of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) of which the Museum has a notable group, remarkable both for their size and their quality.

The paintings on silk are good, typical examples of Ming and Ch’ing Dynasty artists, but the more worthy Chinese paintings in the Museum are found in Harrison Hall.

The connecting gallery between Upper Pepper Hall and the Rotunda contains some of the outstanding objects in the field of Chinese Art, as well as groups of smaller objects which serve to illustrate phases of importance in the history of Chinese culture.

Two great stone chimaeras1 representing grotesque and fantastic animals face each other in the center of the gallery. Probably executed shortly after 500 A.D., they were originally placed on either side of what is known as the “Spirit Path,” leading up to the burial mound of some Imperial personage. The ample yet supple bodies of these beasts are implicit with mobile force and energy, and though the legs are broken, the effect of great strength and power is still strongly present. While larger ones are still to be found in situ in China, only a single one is known of such high sculptural quality, while merely a few smaller ones are to be found in western collections. As Sirén says of such chimaeras, “They mark a culminating point in the plastic art of China and must be accounted among the most convincing evidences of the artistic genius of the Chinese.”

Museum Object Number: C432

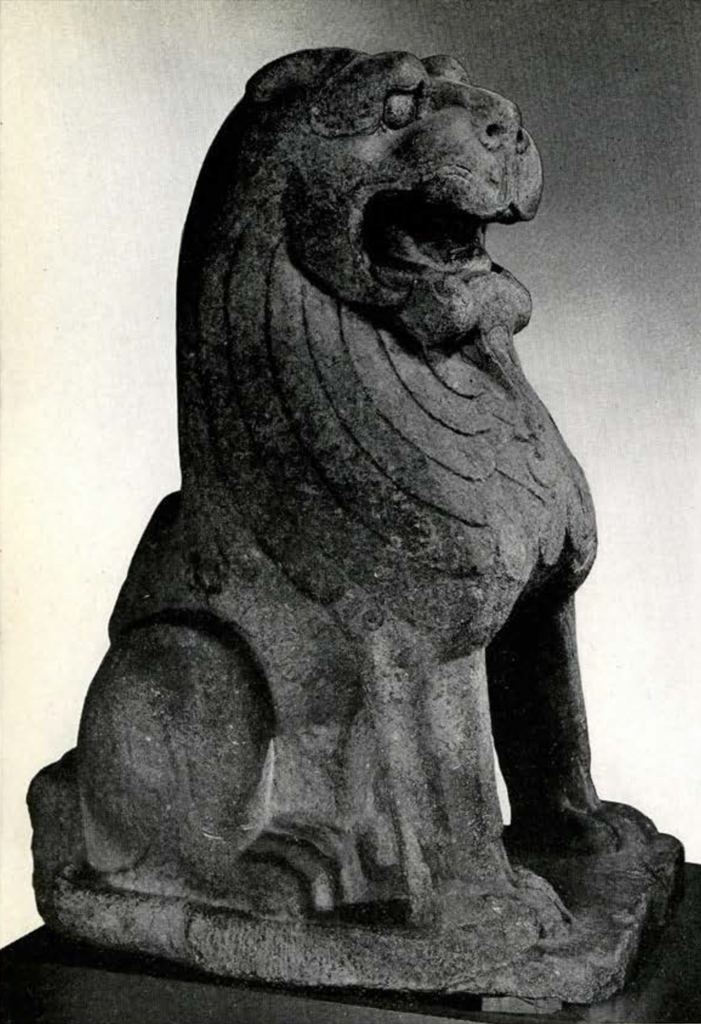

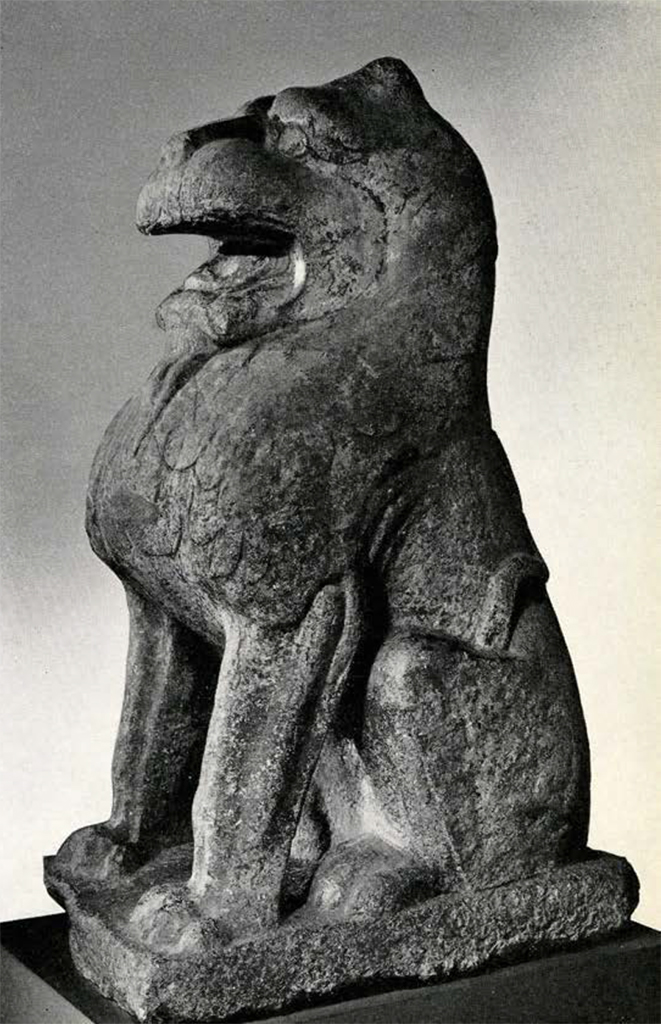

The small seated lion2 in the center of the gallery is perhaps a quarter century later in date, yet it retains many of the vigorous though less awesome characteristics of its larger relatives. The carving is particularly crisp and bold.

A pair of larger seated lions3 flanking the entrance from Pepper Hall would almost inevitably seem to belong to the latter half of the sixth century. They are sturdy and massive, but gain their monumental effect by ponderosity rather than by elegant power. This group of five animals cannot be overlooked by any serious student of Chinese sculpture.

Two vitrines on either side of the entrance to Harrison Hall contain a pair of important glazed pottery flower pots of the Sung Dynasty (960- 1279 A.D.). This particular ware is known as Chun from the place of its manufacture at Chun Chou in Honan Province; the best vessels were probably made at special kilns the output of which was reserved for Imperial use. Each piece from the so-called Imperial kilns is marked on the base with an incised Chinese numeral running from one to ten and probably indicating the size. The Museum’s pots are marked san (three) and few pairs extant are of higher quality. Chun has a body of porcellaneous stoneware and a characteristic thick and opalescent glaze sometimes predominantly lavender blue, sometimes predominantly a rich purplish red, but always with the underlying elements of the opposite color to enrich the sumptuous appearance of the pieces. The pair here exhibited illustrates both types.

Museum Object Number: 40-35-4

Image Number: 1397

Of the four wall cases, one of those to the west usually contains examples of early carved jades, mostly ritual implements found in tombs of the Chou (1122-249 B.C.) and the Han Dynasty (206 B.C.-220 A.D.). These are interesting for the light they shed on early ceremonial customs and for the fine quality of the carving displayed. The other case to the west is usually installed with a selection of Ordos Desert and East Siberian bronzes, weapons, harness trappings and the like. These are executed in the so-called “animal style” with motives long popular among the nomadic peoples of Eastern Europe and Northern Asia.

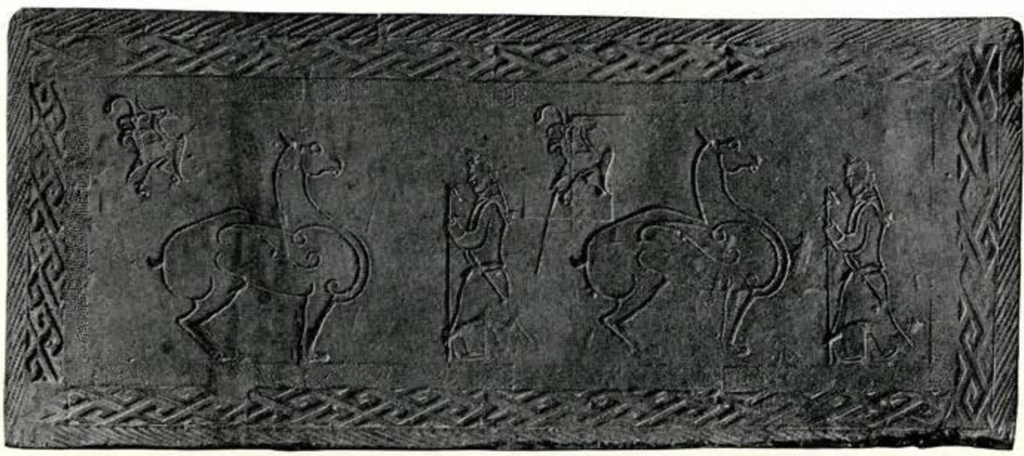

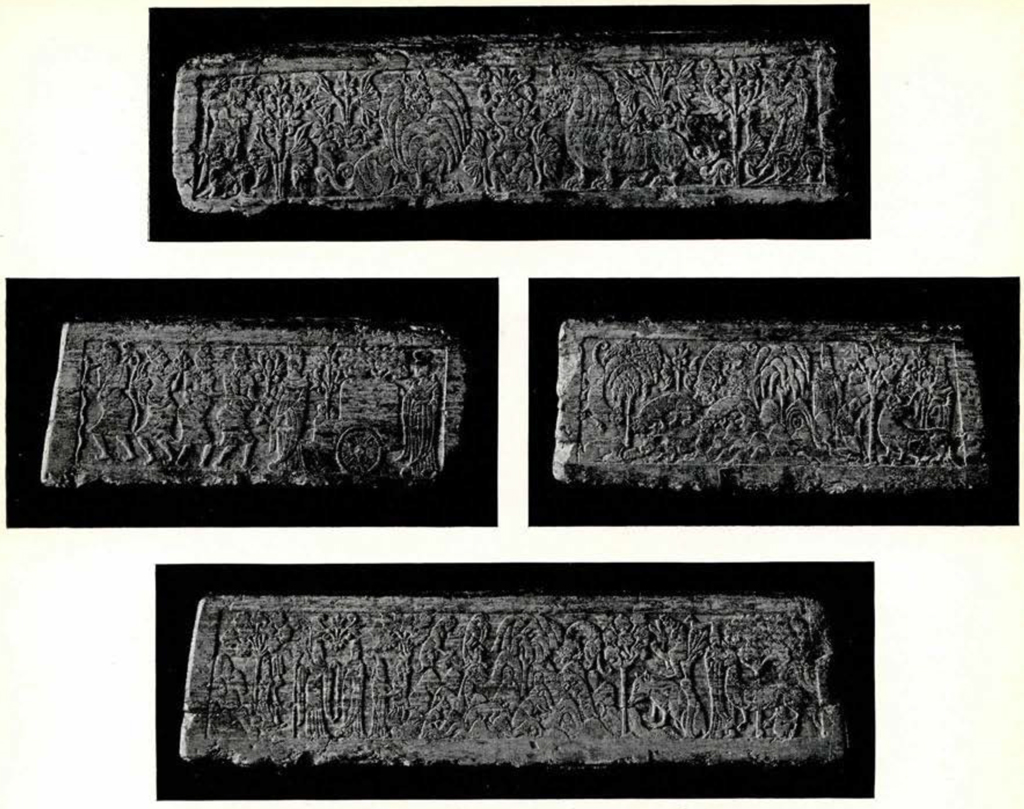

The long stone relief4 of the Han dynasty (206 B.C.-220 A.D.) depicting horsemen and chariots is a notable work of early picturization. Little has come down to us, naturally, to give a clue to the art of the Han painter: reliefs such as this, therefore, are the only bases we have for judging the pictorial art-which must have existed-of this early epoch. One must inevitably feel in this relief a sense of the robustness of the age when horsemanship and the “romance of the road” meant so much to the ruling classes. It is a relief of great quality. The inscription (in singularly plain characters of the Han dynasty) reads: “May this dwelling be used for ten thousand years,” and makes plain that the stone made part of a sarcophagus.

In cases to the east are exhibited small but fine specimens of pottery and porcelains from the Sung Dynasty down to the reign of K’ang Hsi (1662-1722 A.D.) of.the Ch’ing Dynasty, selected from the considerable collection in the possession of the Museum, the group of blue and white porcelains, notably a typical “hawthorne” ginger jar, are of particular note.

Museum Object Number: C412

Image Number: 1533

Museum Object Number: C413B

Image Number: 1534

A fine grey tomb-tile of the Han Dynasty (206 B.C.-220 A.D.) stands on a pedestal between the west windows. It bears simple but vigorous stamped designs and was used, with others, to line a tomb.

On the transverse walls are several examples of early Buddhist wall painting from the Turfan Oasis in Chinese Turkestan. From the sixth to the ninth century Turfan was an important center on the great trade route from China to the Western countries and many temples came into being, the walls of which were copiously decorated with wall paintings of Budd- hist religious subjects. These sites were exhaustively excavated by the German scholar von le Coq, and the bulk of the wall paintings he retrieved are housed in the Museum für Völkerkunde, Berlin. The Museum’s specimens were among those brought back by him. There is a rather strong Indian influence to be seen in the style of the paintings and in the iconography of the subjects, and it is interesting to compare these fragments with the later (but more fully Chinese) wall paintings in Harrison Hall and with the important short handscroll5 on coarse cloth framed and exhibited on the left jamb of the entrance to the Rotunda. This latter painting of Buddhist deities is said to have come from Khotan, Western Chinese Turkestan, and is probably of the tenth or eleventh century; it is of comparable interest to the Turfan wall paintings for the foreign influences to be detected in its composition. Unfortunately it could not be adequately photographed for reproduction.

The dignified architectural treatment of Charles Custis Harrison Hall provides a fitting and harmonious setting for the major part of the Museum’s noted Chinese Collection. The Hall is ninety feet in diameter and the apex of the dome a like distance from the floor.

Museum Object Number: C691

Image Number: 1432

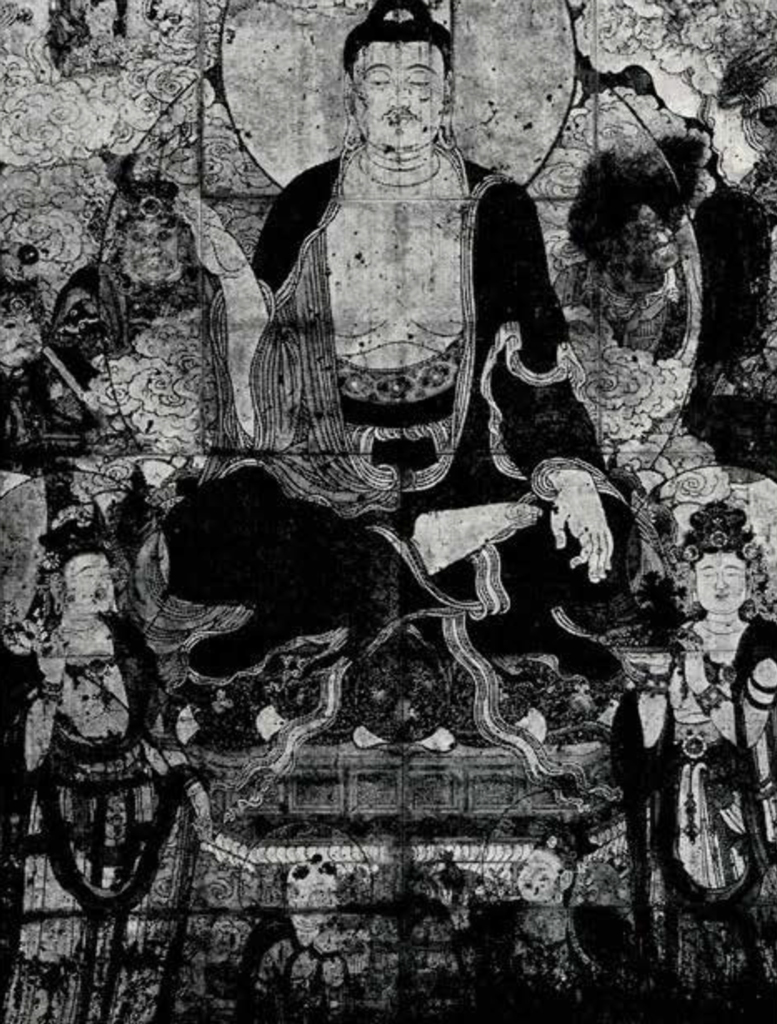

Dominating the hall opposite the entrance are the two great wall paintings from the Moon Hill Temple in the province of Shansi.6 It is difficult to fix upon a satisfactory date for these gigantic compositions; they evidently follow closely the artistic traditions of the great T’ang Dynasty (618 to 906 A.D.) and yet contain elements indicative of a considerably later date. It would seem safe to assign them to some time between the beginning of the fourteenth and the end of the sixteenth century. Their date is of less moment than their artistic quality which is very high. The central figures in each panel-the one on the right being the bodhisattva Amitabha, that on the left, Maitreya-are treated with a majestic repose that is an ingenious foil to the crowds of minor, restless deities, guardians, attendants and children that gather round the bases of the thrones. The excellent handling of the drapery and the harmonious blending of the colors are noteworthy. It is interesting to compare the competence of the drawing in the great wall paintings with the untutored efforts found in the fragments from Turfan-a competence, however, that has perhaps obscured a fervent spiritual quality.

On either side of the entrance door are two particularly charming small statues in grey limestone.7 They represent bodhisattvas and were executed about the end of the eighth century, possibly a little later. They are typical of the rich quality found in the developed sculpture of the middle of the T’ang Dynasty (618-906 A.D.). It is interesting to compare these statues with those in Harrison Hall that pertain to the dynasties immediately preceding the T’ang. All the qualities characteristic of primitive sculpture the world over- qualities that give the primitive Buddhist works from China their particular charm-have been in these two small figures supplanted by the sophisticated ability of the T’ang makers of masterpieces. Many patches of original color still remain on these figures reminding one that such sculptures, when new, were almost invariably brightly painted.

Museum Object Numbers: C688.10 / C688.11 / C688.12 / C688.13 / C688.14 / C688.15 / C688.16 / C688.17 / C688.18 / C688.19

Image Number: 1484

Turning to the right upon entering the hall one finds upon the wall a further group of wall paintings, smaller-and earlier-than the great panels referred to above. They are particularly attractive for their graceful lines and their soft coloring. It seems safe to assign them to the latter half of the Sung Dynasty, the twelfth or thirteenth century, one of the finest eras in the history of Chinese painting. Several other examples in this series are extant and the whole group of figures in their original position must have made beautiful some temple wall with a beneficent procession of appealing deities at whose feet children scampered carrying offerings of flowers and fruit.

On a pedestal between these frescoes is a figure depicting the Buddha in Meditation8 executed in the subdued gold of dry lacquer. The casual visitor may easily be inclined to glance at it and pass it by, seeing little that is arresting in the slight grotesqueness of its attitude, and the redundant quality of its draperies. Yet it is a piece of marked importance and of sincere aesthetic quality. The drapery is busy, with complicated scrolls and folds and convolutions, the pose is probably oddly exaggerated, but these mannerisms are, almost certainly, accented just to mark the extraordinary calm of the countenance, the complete abandonment of the holy mind to meditation. It is a piece of sculpture that requires re-seeing to appreciate. To fix a date for this dry lacquer statue presents almost insurmountable difficulties: it could be Sung and it might be Ming, but such a statement still leaves a leeway of five hundred years, which is a disturbing length of time for those who like their dates more precise. We are, therefore, constrained to say that it belongs to the Yuan Dynasty, the time of the Mongol supremacy (1280-1368A.D.), which is characterized, especially in sculpture, by a revival of T’ang-like vigor, impregnated some-what with the sweetness of Sung. This seems on the whole an adequate artistic pigeon-hole to which to assign this piece. Let the reader beware, however, of the usual Yuan attributions. It is a too convenient oubliette in which to thrust pieces difficult to date. Actually the Museum’s dry lacquer Buddha in Meditation needs no scholarly bush to be appreciated.

Image Number: 2394

The most striking feature of the pair of Tomb Doors9 that stand against a pilaster to the left of the Buddha in Meditation are the Guardian Figures carved in high relief. Of especial importance is its curved lintel engraved with a highly decorative pattern of phoenixes, an unusually beautiful example of this technique, pertaining probably to the end of the sixth century. The deeply cut chimaera masks support original iron ring-handles, while at the bottom two gentle dogs are engraved facing each other-representations, perhaps, of the tomb owner’s especial pets, eternally guarding the entrance to his resting place.

The various groups of large tomb figurines, glazed and unglazed, in this and other parts of the Hall are of importance for their size and their technical perfection. The guardian knights with horrific countenances designed to ward off attacks of malevolent demons, the dignified officials to accompany the spirit to the afterworld, the horses and camels for riding and transport, all these are masterpieces of the potter’s art, and as sculpture, typical of the vigorous realistic quality which made the T’ang Dynasty great in this field.

At the center of the right wall is a trinity of large stone figures. They possess an aloof dignity perhaps unequalled in other examples of sculpture of comparable date that have been brought from China. They are, upon good authority, said to come from the Nan Hsiang T’ang cave temples in Honan Province. While they bear no inscriptions it is not difficult to assign them to the North Ch’i Dynasty (550-577 A.D.), a short-lived epoch, but one artistically well defined in Buddhist sculpture: the early primitiveness, with all its unsophisticated charm, has been superseded by the grandeur and dignity of accomplished workmanship, yet it still lacks the technical supremacy of T’ang figure sculpture. The flanking statues10 are bodhisattvas, of commanding presence and superior mien; the central figure11 is of a priestly attendant holding between his palms the bud of a lotus blossom; though slightly scornful of mortal worshippers his bearing is-as it should be-more amenable to prayerful approach than the bearing of the bodhisattvas. Of this series of figures, the Metropolitan Museum has one on loan, and two or three isolated heads are included in other public collections. No trinity such as the Museum is able to exhibit has, however, been brought together.

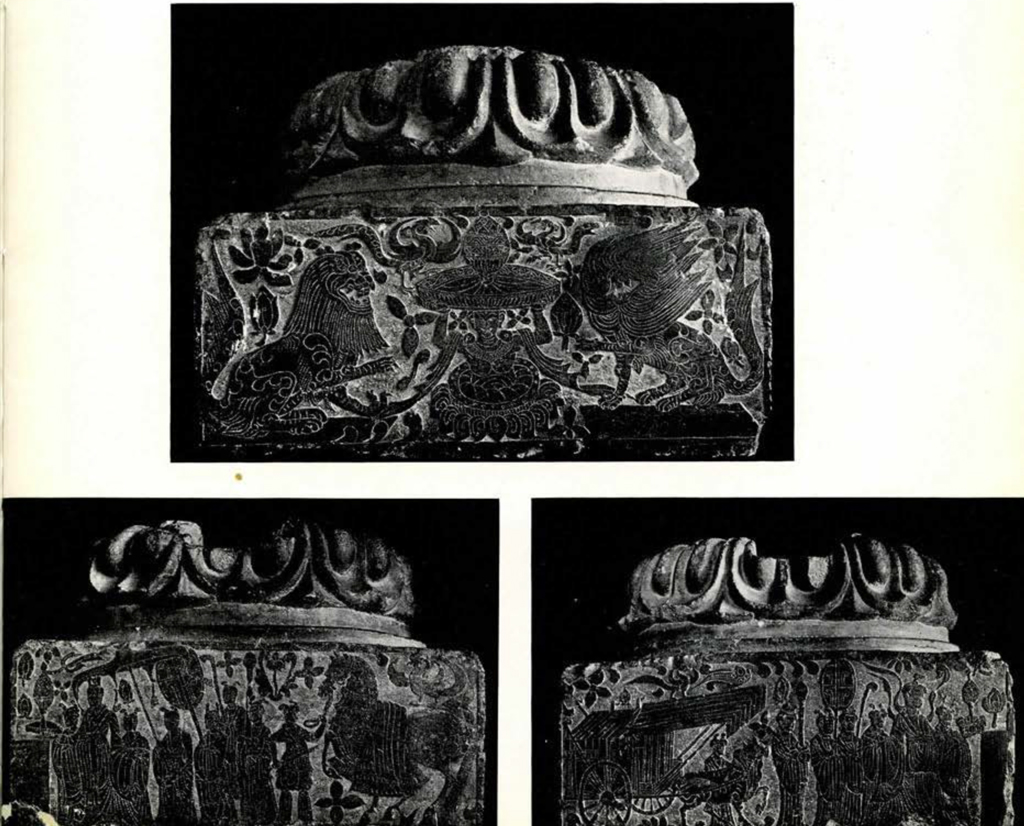

In front of the trinity, on pedestals, are three important stelae-bases which deserve recognition. Though the monuments which they originally supported have disappeared-doubtless destroyed in the periodic upflares against Buddhism-the bases in themselves are valuable documents and worthy works of art.

In this general connection it must be borne in mind that, almost without exception, works of Chinese sculpture that have come down to us have been hewn out of, or hauled bodily away from, their original settings. This immensely complicates our efforts to attribute correctly their provenance and date. Those pillaged from Yun Kang or Lung Mên we can fairly safely assign-as we could figures from the façades of Nôtre Dame de Paris or Chârtres- but when it comes to minor sites which were, too, well furnished with stone sculpture, we are very much at sea: stylistic dating remains our only anchor, and this we throw overboard, in many cases, and cling to as long as we may.

To return to a discussion of the three stelae bases attention perhaps should be especially drawn to the one in the center, 12 given in memory of Randal Morgan. It is carved on three sides in low relief with scenes from the life of the Buddha. The quality of the carving is of high order and, though it bears no inscription, on stylistic grounds it can be assigned to the last half of the sixth century. The front is decorated with the usual incense burner or reliquary guarded by lions and personages of demoniac character. But the free quality of the carvings on the other faces gives us a hint as to what the art of the landscape painter was like at this remote epoch, from which little in perishable material has come down to us.

Museum Object Number: C453

Image Number: 1526

Museum Object Number: C452

The base on the right, 13 surmounted by a crisply carved lotus-petal socle, slotted for the stela long since disappeared, is different in character; its front face has a small figure holding the reliquary or incense burner flanked by guardian lions with swirling manes. On one side is engraved a scene depicting the donor of the stela-evidently a person of quality-marching under a great parasol with a bodyguard of various attendants, the last of whom is leading a richly caparisoned charger. On the other side is the donor’s wife in her two-wheeled cart accompanied by mincing handmaidens. The costly trappings of the animals, the flowing robes of the courtiers, the admirable placing of the various figures make these two panels veritable masterpieces of early Chinese linedrawing. On the back it bears a long inscription with a date corresponding to 525 A.D.

The third of the Museum’s important stela bases14 is again to be rated, apart from its intrinsic interest, as an important artistic document. Whereas the Randal Morgan base was carved in low relief and the base dated 525 A.D. was executed largely in engraved technique-the background being cut away and only details rendered with simple incised lines-this base is wholly a line engraving on stone with no attempt made to give the scenes anything but plain pictorial quality. The scenes are not hugely exciting, it must be confessed, being mainly episodes in the life of the Buddha with groups of figures in formal poses, rendered according to the confining canons of the Buddhist religion of the times. But the designs along the bevelled edges-dragons, phoenixes, masks and lotus scrolls-reveal the artist’s real fire and creative spirit. The base is not dated, but because of the tightness of the composition, it must be later than either of the other two bases heretofore described, and can, therefore, be assigned, with considerable confidence, to the early years of the T’ang Dynasty, about 650 A.D.

Museum Object Number: C405A

Image Number: 1425

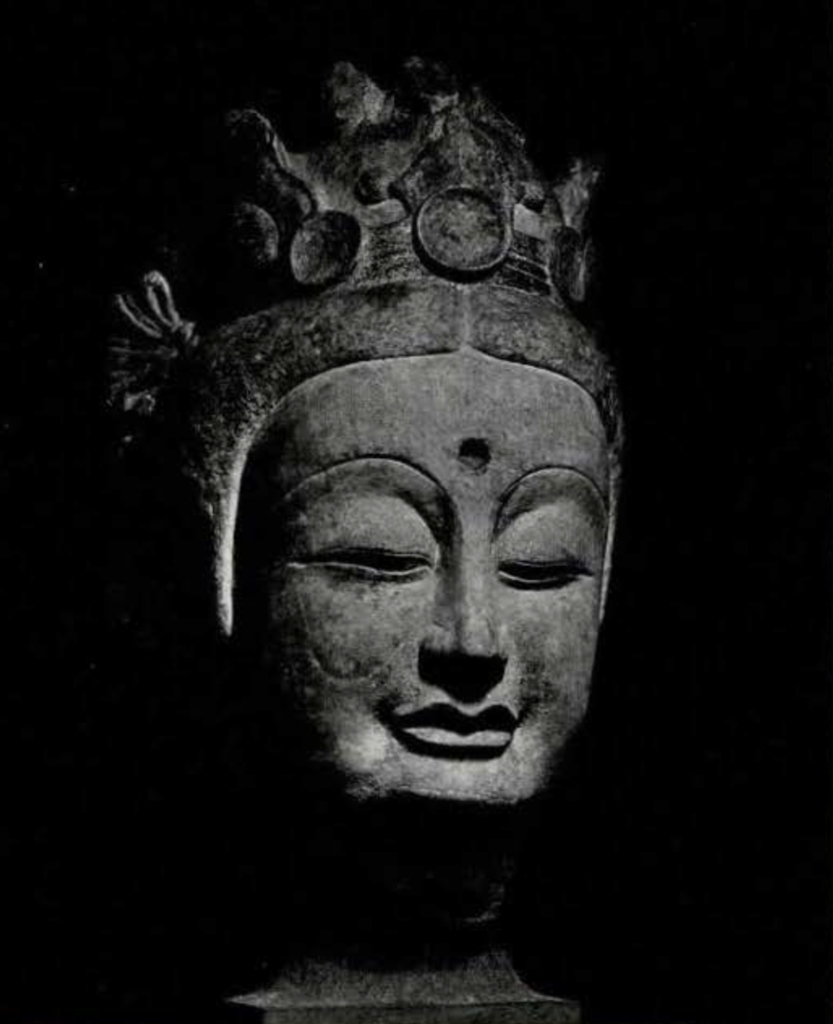

On high pedestals against the wall between the great wall paintings and flanking a superb carpet of the reign of K’ang Hsi, are two great stone heads of bodhisattvas, 15 the gift of James B. Ford. These are of simple majesty and would seem to belong to a period just preceding the T’ang Dynasty.

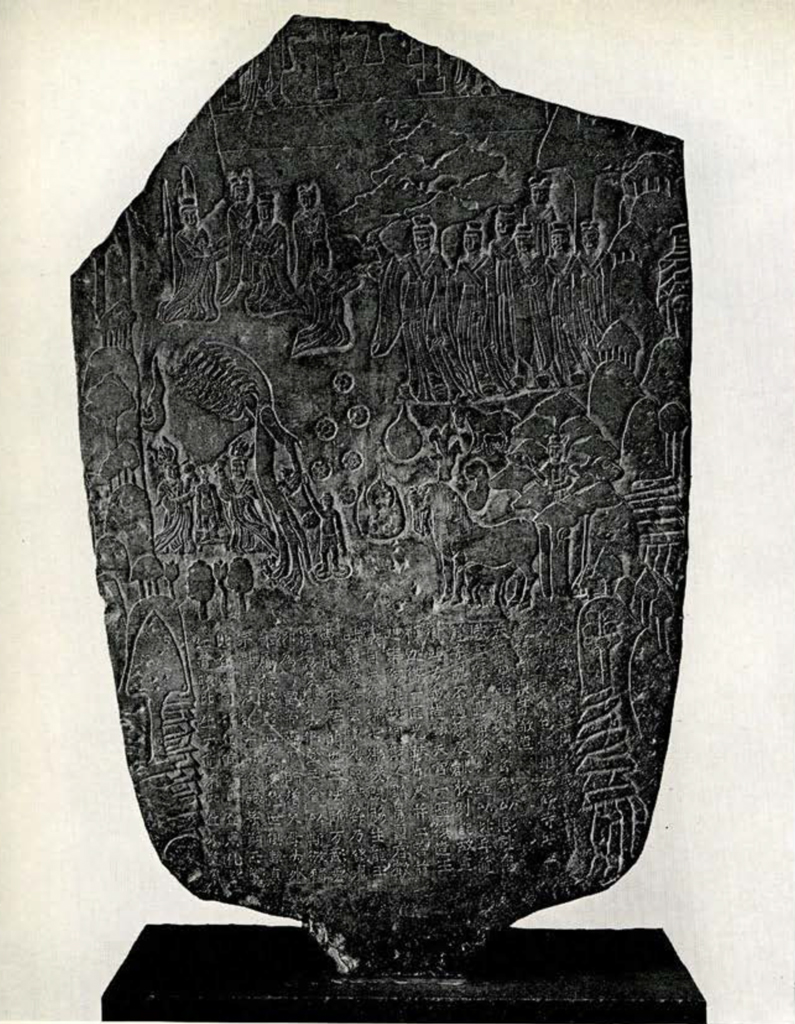

Set forward between the two colossal heads, and on axis with the entrance to Harrison Hall, is found the famous Maitreya stela16, one of the greatest documents of Chinese Art exhibited in the Museum and one of the most beautiful examples of primitive Chinese stone sculpture extant; this also was the gift of Mr. Ford. It is dated 514 A.D. and Buddhist monuments of so early a date are rare. The figure is that of the Maitreya or the coming Buddha. The conception, because it is primitive, is full of a gentle spirituality. One must remember when looking at such sculpture, whether it be from the east or the west, that the artist was only interested in carving something that would express his deep religious belief in the existence of a benevolent supernatural presence; he was not at all endeavoring to represent a god “in his own image”, but actually-whether consciously or unconsciously (who shall say)-striving to express something more lofty, more beautiful than ever he had seen on earth. No element at all in this piece of sculpture is a slavish copy of nature. The fall and undulation of the soft robes are such that no silk or gossamer of the world ever assumed, the Maitreya’s hair, his face, his hands, his feet are those of a heavenly being, not to be judged as replicas of such features in mankind. Bear this concept in mind when viewing this and pieces of similar date and they will take on new interest, new beauty. To realize this attitude of the early Buddhist sculptor is to go nine-tenths of the way towards appreciating the fundamental beauty of his concept. It is far better than merely to murmur such meaningless cliches as the “ineffable calm of Oriental Art” or “the inscrutable beauty of the East.”

Museum Object Number: 40-7-1A

Image Number: 1418

There is much color still on this Maitreya stela. We cannot safely say these are the original pigments, but in all probability the hues closely follow those originally applied and hence, though when first dedicated it was unquestionably more brilliant, almost to the point of garishness, we have today a fair approximation of its appearance a decade or so after it was carved.

On the back of the stela there is engraved at the top a group depicting Sakymuni and Prabhutaratna, and fifty-four little seated figures of the Buddha, perfunctorily outlined in the constant oriental belief that reduplication of images proportionately increases virtue. There seems to be no evidence whatsoever that any later hand was concerned with restoring this stela, either on the face or the back; this makes it particularly important. The inscription is in perfectly acceptable late pre-T’ang characters and there seems no reason to doubt the dating therein fixed.

The pair of Guardian Kings17 flanking this stela deserve special regard. Vigorous, domineering and forthright, they provide an interesting contrast with the subtlety of the Maitreya figure. In date they are perhaps two hundred years later and can be assigned to the first half of the eighth century, and come from the well-known site of T’ien Lung Shan. The figures are executed in the full round and are of the characteristic coarse light grey limestone typical of sculpture from this area. They stand solidly on low, shaped bases which in turn either rested directly on the cave-floor or possibly on plinths at the entrance to a cave. Originally they were apparently fastened to the floor or held steady against the wall by metal clamps, holes for which are visible at the back of the base of each figure.

Museum Object Numbers: C150 / C151 / C113

Image Number: 1300

Just under life-size they stand armed, cap-a-pie, in the traditional leather and quilted uniforms of warriors of their day. Much of the earlier coloring remains: whether these patches are contemporary with the actual carving or not we have no means of telling-certain areas are covered with a slightly raised basketwork pattern in gesso, which was painted red and gilded, a technique apparently developed during the T’ang Dynasty. The remains of this surface decoration and of the colors enable us to recreate the appearance of the figures when first erected. It should be noted that the nose of each has been broken and later skillfully restored.

Like the other sculpture in this particular group of cave temples at T’ien Lung Shan, there is an unusually strong Indian influence in the features of these Guardians, particularly to be observed in the one with the crisply carved mustachios and chin whiskers. The armor, however, is typically Chinese and bears a close similarity to that found on pottery tomb figures of guardians that belong to this same epoch.

Of the Chinese paintings exhibited nearby, it is only necessary here to mention the handscroll “Spring Morning in the Palace”.18 It is one of the outstanding Chinese paintings in America. It is attributed to Chou Wen Chu who flourished in the later part of the twelfth century, but from literary and stylistic evidence this attribution seems doubtful, and it is generally accepted that it is an adaptation of Chou’s original painting executed perhaps a half century later. Its grace and its elegance need no laudatory paragraphs. It is of interest to draw attention to the fact that two other portions of this painting are known: one belongs to Dr. Bernard Berenson of Florence, Italy, the other to Sir Percival David, Bart., of London. Even with these priceless fragments extant there is still some of the original painting unknown to us.

Museum Object Number: 34-7-1

Image Numbers: 1387-1396

It is not requisite to have before one the whole painting, however, to appreciate its unusual refinement and quality. As, of course, is the case with all handscrolls, it was never intended to be viewed as an entirety, but to be unrolled before a few appreciative connoisseurs who stood about, with bated breath, and enjoyed, section by lovely section, as it passed between the proud owner’s hands. Thus each group of figures of the Palace Ladies is a composition in itself. The figures represent the well-cared-for-often opulent-women of the court of the Sung emperor with roly-poly children playing at their feet and puppy-dogs rolicking about.

In every part of the scroll the steady, gracefulness of the lines indicates that it was no slavish copy; no copyist, carefully following a great original, can maintain this firmness. Wherefore we cannot conceive that the Palace Ladies is a replica of an original by Chou Wen Chu. It is, of course, not an unusual subject and was a favorite, even before Chou’s time, but his painting (which has not come down to us) apparently made such an impression and established such a reputation that the painters that followed him whenever they attempted the subject, did so with the pious hope that their accomplishment would be as fine as his. If the new version achieved any measure of success, it is easy to imagine the artist’s scholarly friends saying-as highest praise-“why, your scroll is a Chou Wen Chu”, and even pen dedicatory descriptions to this effect. Thus, with no thought of fraud, often times later connoisseurs have been misled.

If the unknown author of the Palace Ladies wished to hide beneath the cloak of his great predecessor who are we to deny him the privilege? In doing so we join the scholarly band of those who imply that even Chou himself could not have done better.

Museum Object Number: C145

Image Numbers: 1399-1401

More than a passing glance should perhaps be given to the back of the light grey limestone stela19 that stands in front of the large wall painting on the right. The face of the stela is somewhat dull, and perhaps has been recarved, but the back carries delightful scenes of the birth and early life of the Buddha, freely and charmingly rendered in the manner of the sixth century.

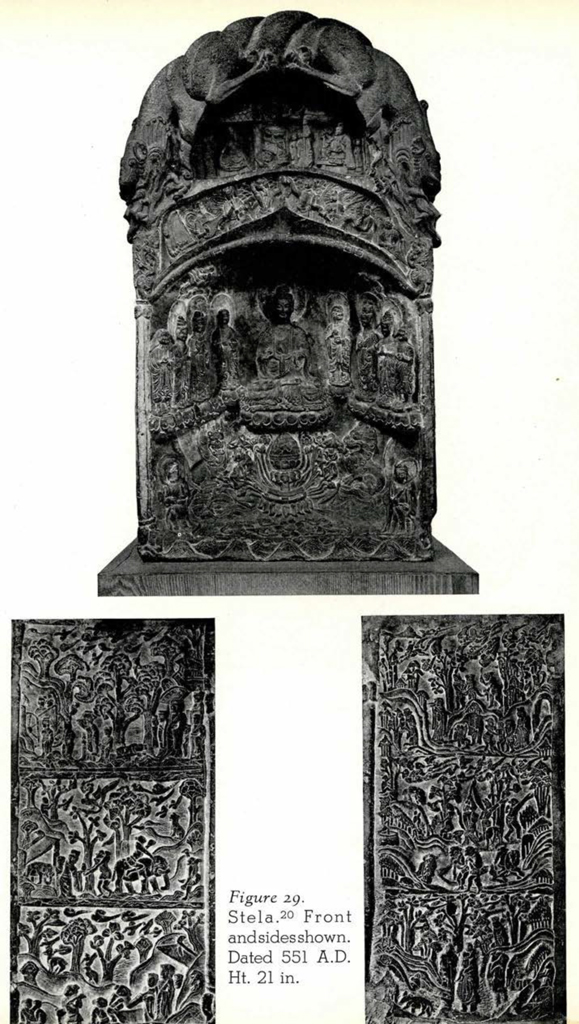

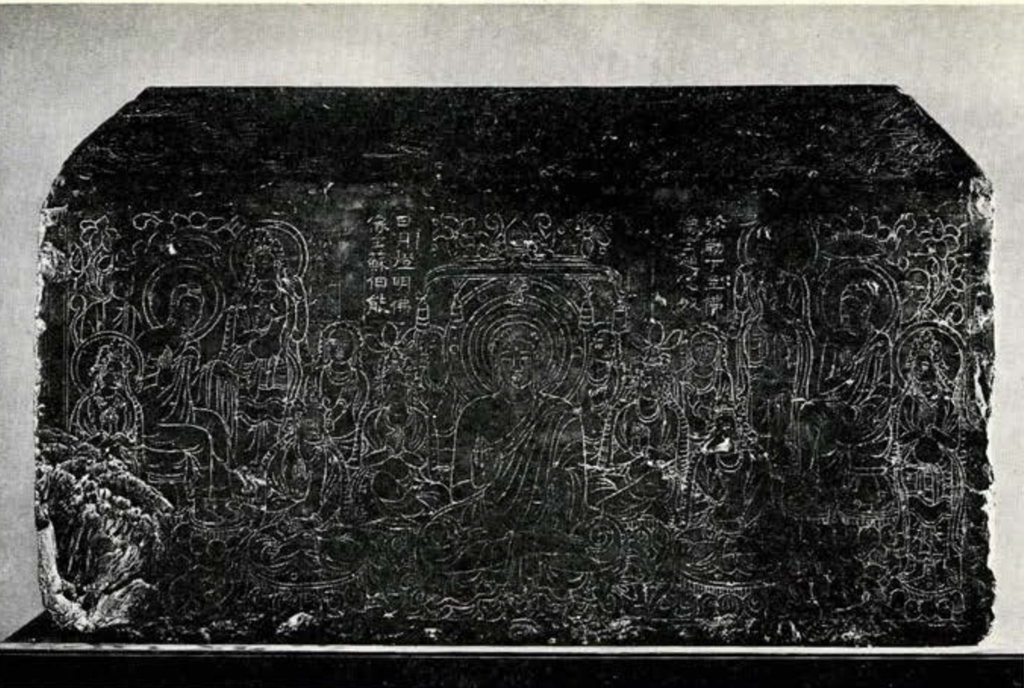

On the opposite side, on a pedestal in front of the other wall-painting, there is a stela20 that merits fuller discussion. From the triple dragons bracing their legs and arching their scaly coils over the top, to the little lapping waves at the bottom, the whole composition of the frontal panel is admirably organized and executed with precision and skill. The band of dancers and musicians above the main niche is a particularly happy conception, an interlude as it were, between the two serious religious groups above and below. The one above, in a panel deeply carved beneath the bodies of the dragons, illustrates the oft-told tale of Manjusri’s visit to Vilmakirti, while in the main niche below sits the Buddha Enthroned flanked by his monks, by bodhisattvas and priests, all standing on lotus pedestals and all pretty well pleased with themselves. The two kitten-lions perched next the halos of the bodhisattvas seem to be peering down to catch a glimpse of their full grown, ferociously benign relatives sitting on the margin of the sea, and guarding the incense burner which is surrounded with little lotus buds from some of which peer newly reborn souls.

The sides of this stela have scenes from the life of the Buddha arranged in panels: these are very similar in content and in treatment to the parallel scenes on the Randal Morgan base. Upon the back is a long inscription-carved in the 40th year of the reign of Chia Ching of the Ming Dynasty (i.e. 1562 A.D.) which sets forth that this monument was originally dedicated in the second year of the Northern Ch’i Dynasty, that is 551 A.D. There seems no reason to doubt this Ming statement, for the piece has all the characteristics of North Ch’i sculpture, but one is inclined to suspect that the Ming stonecutter, when he was bored with carving the inscription, could not resist going around to the face of the memorial and exercising his skill in elaborating the draperies, touching up the countenances of the deities and making more curly the lions’ manes. There is a hint of the Ming craftsman’s love of complexity that undoubtedly suggests this happening.

Museum Object Number: C144

Image Number: 1428

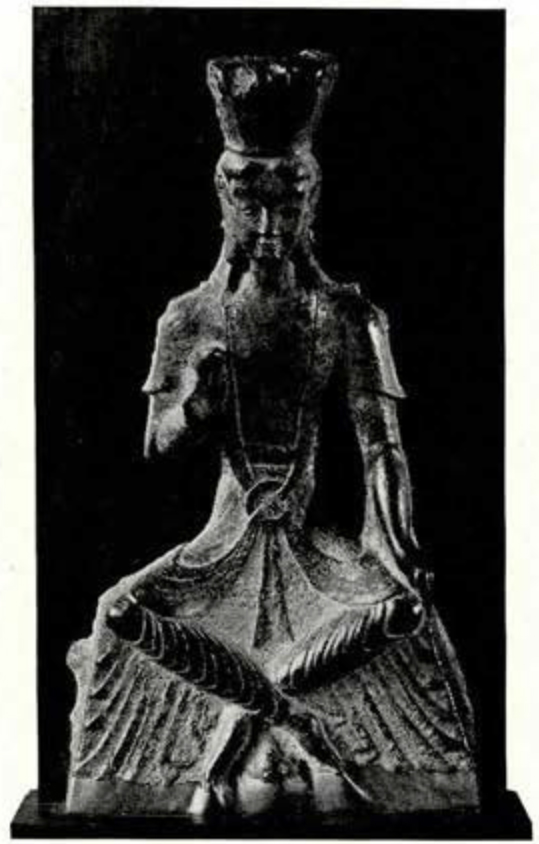

A particularly appealing and charming piece, representing a cross-legged figure of the Maitreya21 comes from the noted caves of Lung Mên, in Honan Province, long famous for the artistic merit of their early Buddhist sculptures.

This seated figure comes from a cave which contains a dedicatory inscription with a date corresponding to 512 A.D. The cave is one of the most beautiful at Lung Mên, its every inch of surface once ornamented with sculptures, which, though primitive in concept, are nevertheless as sensitive and spiritual as anything ever wrought by the early Chinese Buddhists. The Museum’s figure measures up to the best. It is a representation of the Buddha Maitreya-the compassionate one-who was particularly venerated by the early Chinese Buddhist and widely represented in the chapels of Lung Mên and Yün Kang. He was in this epoch regularly represented in the pose we here find him, seated on a high throne with knees outspread and ankles crossed. He seldom bears any distinctive attributes, and his costume consists of a small jacket about the shoulders, the front edges of which are prolonged to make streamer-like scarves which are crossed through a ring at the waist and whose ends fall to the lap and over his knees. A pleated skirt, tied in at the attenuated waist, falls in lovely sharp folds across the thighs and legs and spreads out over the throne. Upon the deity’s head a high flaring crown rests on the parted hair which falls in two simple plaits over each shoulder. His right hand is raised in the abhaya mudra, which to the initiated is as if the god were saying “fear not, I am the compassionate one.” The left hand rests idly on his knee.

The figure is carved in the grey limestone characteristic of the Lung Mên cliffs, and it has attained a rich ebony surface by the passage of time. In chiseling the figure from the cave wall, it was apparently broken across at the waist, but here is the only indication of repair or restoration. While the composition of the figure is wholly delightful, it is the expression of the face-so simply rendered, so appealingly spiritual-that gives a special character to this work of an unknown artist working in the early sixth century.

Erected in front of the door to the Upper Egyptian Hall is a tall monument22 in limestone to which age has given a beautiful glossy brown patina. It has been exhaustively published by Helen E. Fernald, and for its iconography one is referred to her article in Eastern Art, volume III. The inspiration for the scenes depicted comes from the Buddhist Sutra called The Lotus of the Wonderful Law which has been referred to as one of the three most influential religious books in the world. The stela is dated 575 A.D. and, though the figures are somewhat rigid and lifeless, the handling of detail shows an obvious advance from the earlier works already described.

In a large vitrine in front of this stela are exhibited a pair of silver bowls and covers23 of unusual character and beauty. It seems inescapable that these were made for the use of some noble family, and the style of their decoration gives them a date in the first part of the Sung Dynasty. The floral medallions, that fill the spaces between the petal-like flutings, are enriched with gold, not plated but burnished into the surface of the silver. The out-curved rim of the cover-it is missing on one of the pair-served as foot when the cover was reversed and made another dish for the serving of exotic delicacies.

Museum Object Number: C284

Image Number: 1265

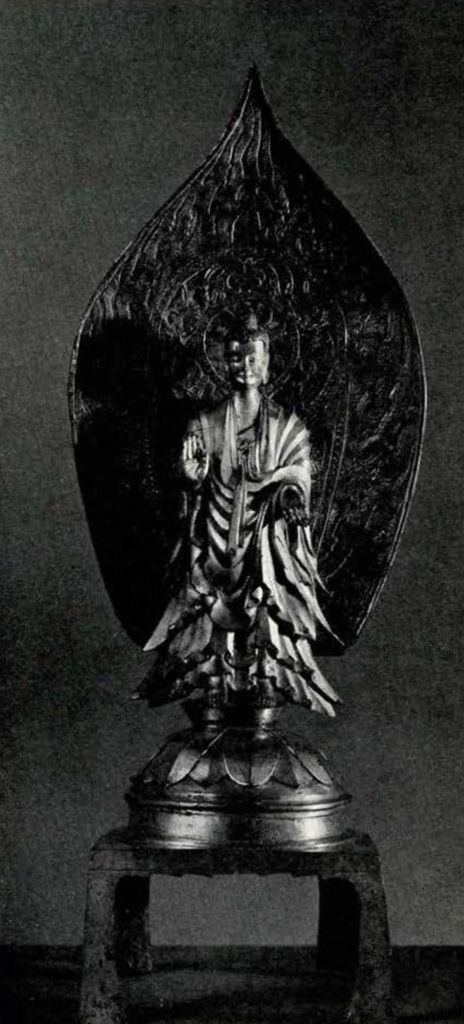

The vitrines on either side of the silver bowls and somewhat nearer the center of the Hall contain two very important gilt bronze statues. Before discussing them, however, attention should be turned to the bronze trinity that stands in the illuminated vitrine in front of the Main Entrance to Harrison Hall. This was given to the Museum by A. Felix du Pont. Mention of this group has been deferred till now since the trinity and the two gilt-bronze figures can most effectively be considered together. The earliest is the gilt bronze Maitreya with the leaf-shaped halo, 23 the gift of James B. Ford. Its pedestal bears an inscription with a date corresponding to 536 A.D. It is the only one that is dated, but there is no question that it is the earliest. It reflects in all its details the rapturous unsophistication of the pre-T’ang religious artists. Very similar is it to the stone Maitreya stela which, it will be recalled, is dated 514 A.D. The handling of the ends of the scarves, the primitive smile, the formalized hair arrangement, are closely similar. Yet the gilt bronze bears the same relation to the stone as does a delicately cut gem to a piece of heroic statuary. Minutely and perfectly wrought, it is a religious symbol “in little” of simple and straight forward loveliness.

Turning next to the trinity24-the figures of which were never gilded and are now covered with a delicate grey-green patina-it will be immediately appreciated that an artistic change has taken place. Indeed about half a century elapsed between the casting of the Maitreya and that of the trinity. The ends of the folds of the scarf have lost their angularity, the draperies have increased greatly in complexity, especially in the case of the flanking Bodhisattva figures, the hands and feet are much more realistically rendered, the primitive smile is on the verge of disappearance. And there is an attenuated loveliness that contrasts with simple forthright beauty of the Maitreya.

We can safely date the trinity in the last two decades of the sixth century, since the style is closely allied to that of the well-known Tuan Fang altar-piece in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, which is dated 586 A.D.- so close is the similarity indeed that the two sets might well be products of the same atelier.

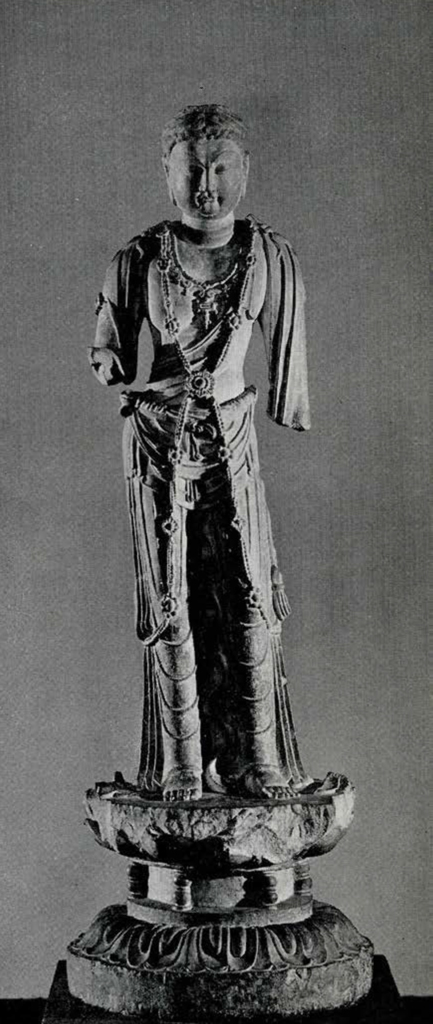

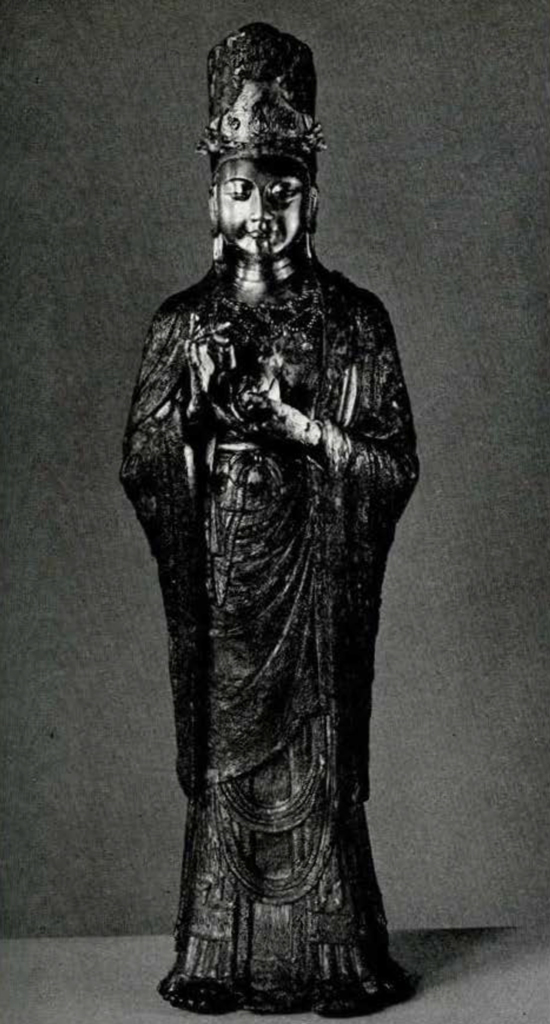

In marked contrast is the larger, and perhaps more immediately comprehensible, gilt bronze figure25 in the third vitrine. This noble figure of Kuan Yin originally gilt all over, of which only certain areas remain, was given in memory of Mrs. Emory R. Johnson. Again time has elapsed and the style of the Chinese sculptor has altered materially. The artist in this instance plainly placed realism above spiritual content, and he achieved to the full what he set out to portray-a majestic figure gorgeously clad in jewels and baubles, rich silk and fine linen, with a benign austerity that should seem to a wealthy patron worthy of his worship. It is difficult to date this figure precisely: one might easily conceive it to be a product of the end of the T’ang dynasty, and yet the high, draped headdress to some might suggest an even later date-perhaps even early Ming. To those who have read so far and have examined the figures in stone and in bronze described above, it should prove an interesting problem to see for themselves what date seems most fit.

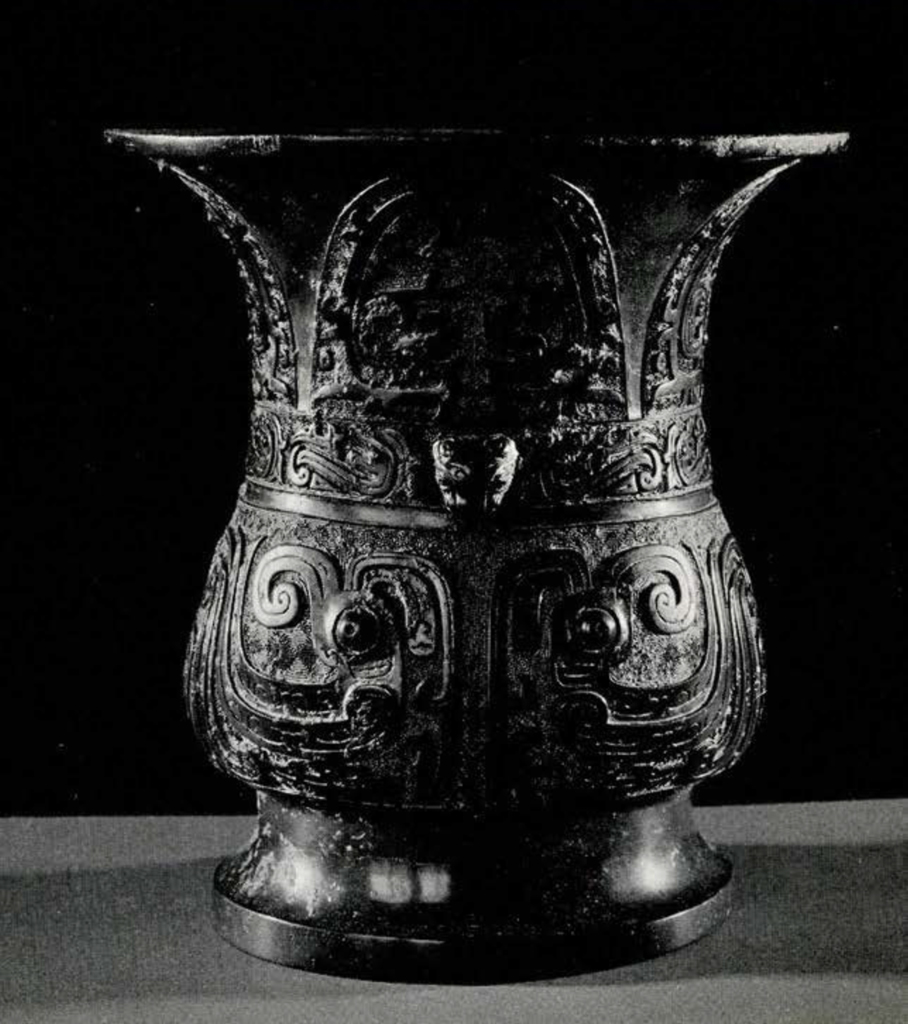

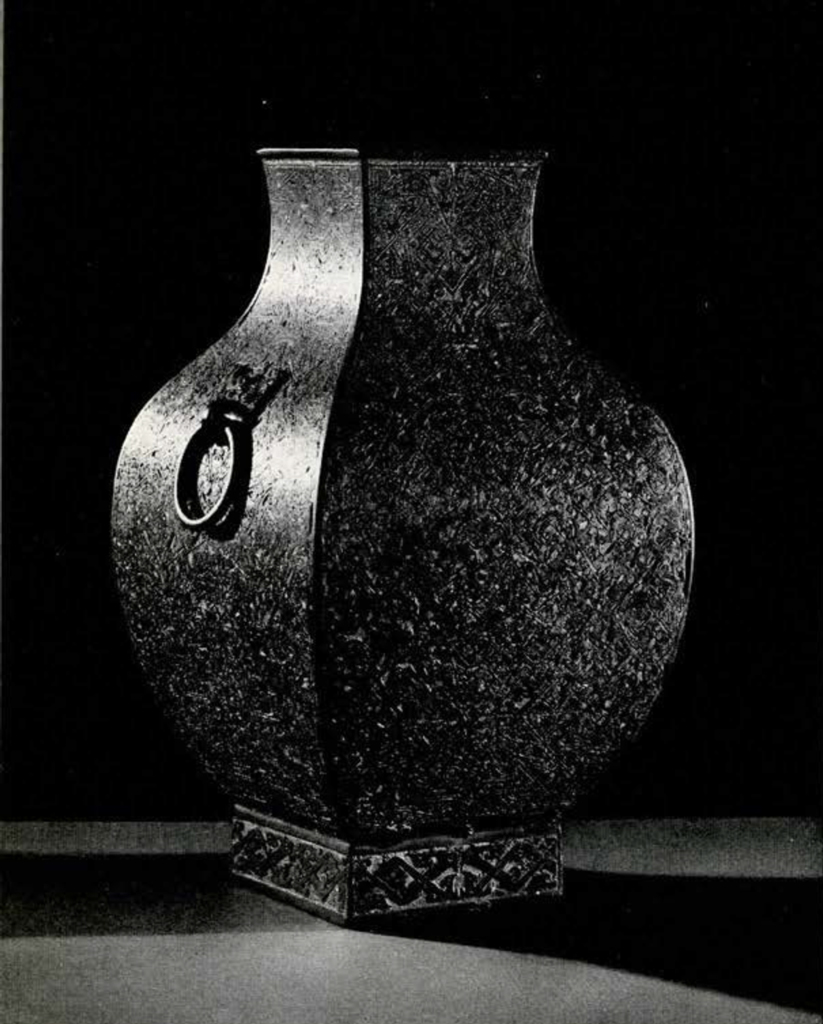

Of the vessels of bronze that are to be found nearby, particularly important is the large square-sided wine-jar26 with an intricate all-over pattern inlaid with malachite. This has an interesting inscription in an early form of Chinese around its base, describing how it was captured by Cheng Teh-Kung. It must, therefore, have been made prior to the third century B.C. and is an extremely interesting and valuable document. In the opinion of Chinese connoisseurs and collectors ancient bronzes and jades have a preeminent place and those with inscriptions pertaining to early epochs in their history are particularly valued.

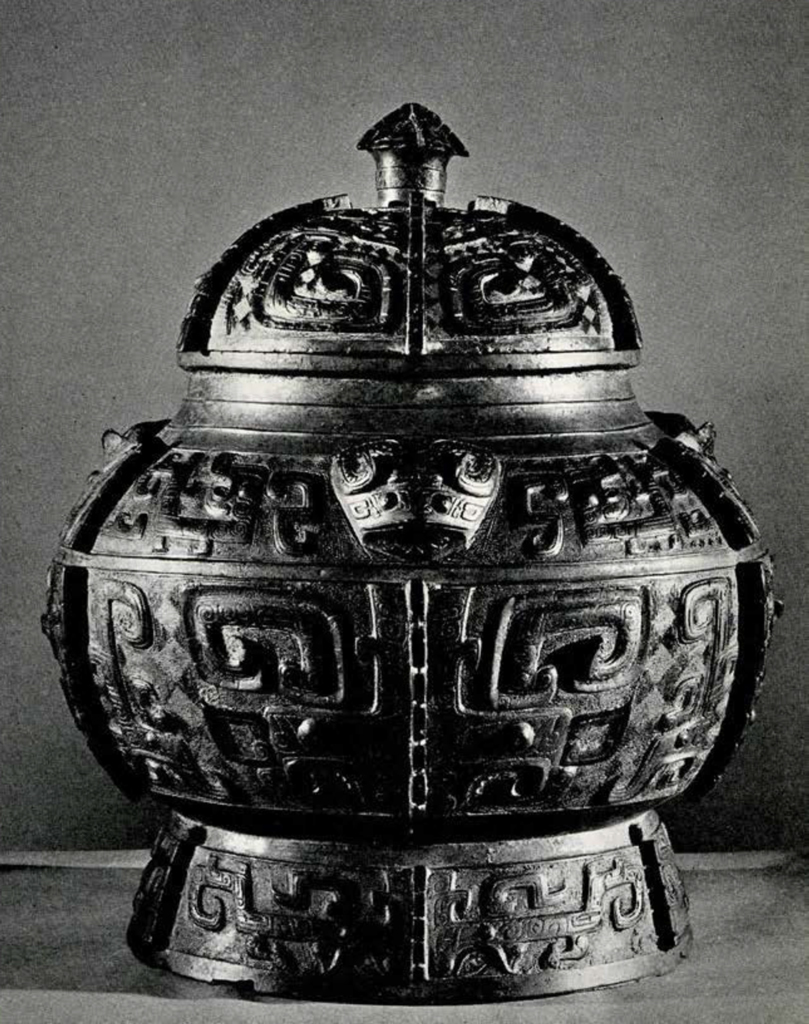

Image Numbers: 1764, 1765

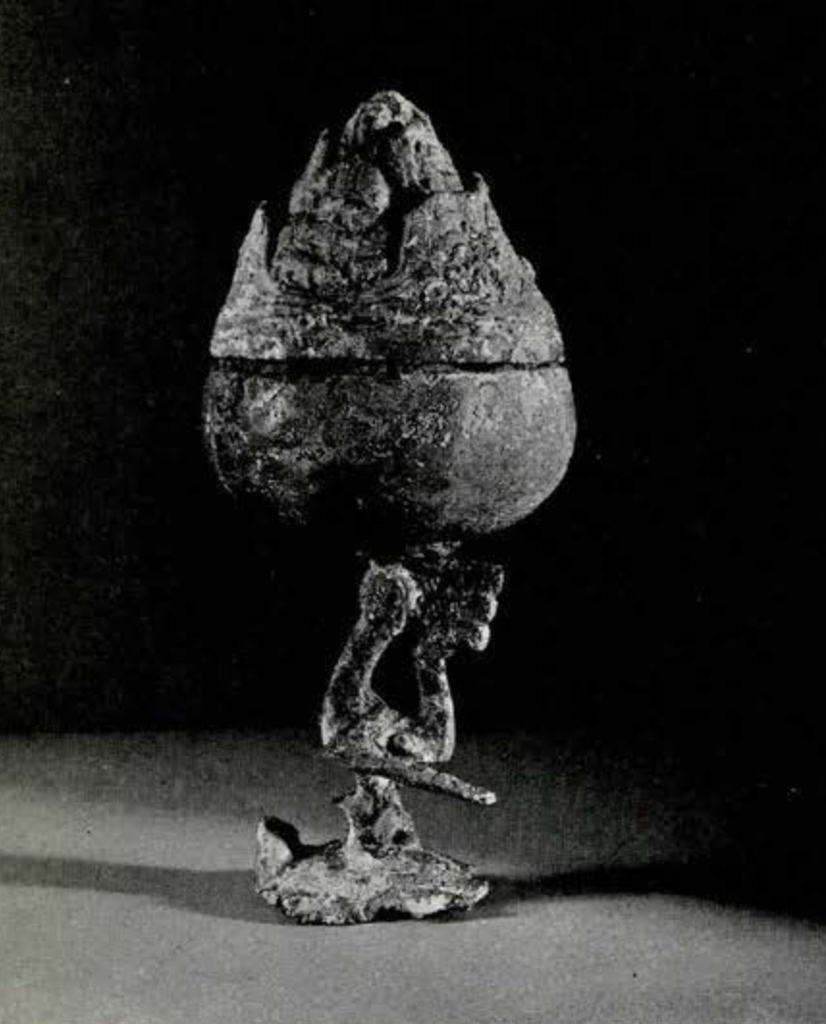

The noble-sized covered jar27 with bold animalistic designs in relief in intricate decorative patterns is a fine example of ritual bronzes of the Late Eastern Chou period 770-256 B.C. This vessel and the large vase of black bronze in the vitrine, with a patina of surpassing brilliance-also of Chou date-were given by Mr. Lammot du Pont. The smaller vase of similar shape29 and the hill censer30 in the same case are fine examples of early casting.

This choice group of ancient Chinese ritual bronzes deserves more consideration than space here permits, since they represent a vital phase in the study of the earliest, and in many ways, the finest, artistic expression of the Chinese, and individually the pieces merit close study.

Against the wall in the northeast quarter of the hall are the two bas-reliefs of the Emperor Tai Tsung’s horses31 which are, of course, among the greatest artistic documents that have come from China. The Emperor T’ai Tsung was the founder of the T’ang Dynasty and one of the few really great rulers in world history. Best remembered perhaps for his military achievements which knit a host of warring states into a mighty empire, he was nevertheless a civilizing force from whom stemmed a large part of the greatness of the Tang Dynasty in government, in literature, and in the arts. When his long reign was drawing to a close he ordered six bas-reliefs carved which should portray his six favorite horses. These panels were to be placed around the base of the tomb he planned for himself near the great capital he created at Ch’ang An-City of Everlasting Peace-in the Province of Shensi. The six reliefs were duly carved five years before Tai Tsung died; four are to be seen in the Provincial Museum in Sian-fu, but the two finest are lodged in Harrison Hall. They were given to the Museum by Mr. Eldridge R. Johnson. The panel on the left, tradition tells us, represents a chestnut bay charger which the Emperor rode when he captured the Eastern Capital in 621. In the course of a particularly bloody foray an arrow pierced its chest, where-upon one of his bravest generals dismounted in the midst of the battle, gave the Emperor his own horse and proceeded to pull out the arrow; an act of chivalry that occurred over thirteen centuries ago and was made immortal in the stone before us.

Museum Object Number: C447

Museum Object Number: C447

Image Number: 1382

The right hand panel represents a charger which was said to be a saffron yellow horse, and, from the arrows piercing its flanks, one that also saw much active combat, but whose presence in a particular battle has not been recorded.

These panels are excellent examples of the realism attainable by T’ang sculptors. The problems of bas-relief are met and adequately solved, and beneath the surface of the stone there seem still to play the muscles and sinews of the sturdy little Mongol ponies that carried so courageously the weight of their great Emperor Tai Tsung.

It is of importance to note on the left-hand edge of the panel depicting the chestnut bay the floral scrolls that apparently once embellished all the borders and edges of these memorials; these designs are, we know, so characteristic of the early sixth century that even the vestige of their presence brushes away any possible argument that these panels are later products.

Finally we come to the glazed pottery Lohan. 32 By considering it at the last, it receives the particular accent that it deserves. It is illustrated in the frontispiece.

Even though blind to its extraordinary artistic quality, one could not but be impressed by it as an achievement of pottery glazing and firing. Even to an age accustomed to great accomplishments of craftsmanship, this figure, perhaps a thousand years old, is a startling feat of ceramic art.

Museum Object Number: 40-35-3

Image Number: 1429

The Lohans of Buddhism make an interesting parallel to the apostles of Christianity. The term Lohan, broadly, means an individual who, having passed through the various stages of saintship, is either fully prepared to become a Buddha or to enter Nirvana directly. The term is, however, usually reserved for the disciples of Sakyamuni (the historical Buddha), and these are commonly referred to in Chinese and Japanese Buddhism as the Eighteen Lohan. Of the set to which the Museum’s Lohan belongs, six are extant: they were discovered cached in a cave near Ichou in Chihli Province and when the first specimens reached Europe they were immediately recognized to be among the noblest examples of Chinese sculpture ever brought to light. It is generally believed that they were made during the T’ang Dynasty, to which certainly they belong stylistically.

In spiritual elegance and intellectual quality no portrait statue-for it seems inescapable that these must have been actual portraits-of any age or land can rival the Museum’s figure. One could write analytical paragraphs in an endeavor to show how the sculptor attained the extraordinary feeling of wisdom, of probity, of forbearance, but these would be a waste of ink and paper; the Lohan is there and speaks for himself with ageless eloquence.

Museum Object Number: 39-20-1A / 38-20-1B / 38-20-2A / 38-20-2B

Image Number: 1138

Museum Object Numbers: 38-32-2A / 38-32-2B / 38-32-1A / 38-32-1B / 38-32-3A / 38-32-3B

Image Number: 1233

Museum Object Number: C243

Image Number: 1785