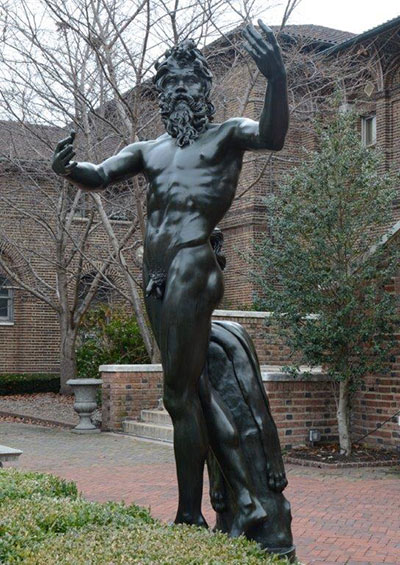

For more than 50 years, visitors to the Penn Museum have been welcomed by a large bronze classical statue, a copy of a work known as the Borghese Satyr, which stands near the reflecting pool in the Warden Garden. is striking figure—with the equine tail and ears characteristic of the part animal, part human mythological creature—appears caught in a dance, with crossed legs and outstretched arms. The satyr is a bronze copy of a marble statue in the Borghese Collection in Rome. How did it come to be at the Museum?

The Borghese Satyr is part of a collection of more than 450 bronze reproductions given to the Museum in 1904 by the Philadelphia department store founder and philanthropist John Wanamaker (1838–1922). Wanamaker joined the Museum’s Board of Managers in 1896 and became one of the new institution’s most generous supporters; he remained on the Board for more than 25 years. The bronzes were made by J. Chiurazzi & Fils, a foundry in Naples, Italy, which was established in 1870 and became well known for its fine bronze reproductions of ancient objects. Almost all the Wanamaker bronzes, although not the Borghese Satyr, are reproductions of objects preserved in the Naples Archaeological Museum and found at the ancient Roman towns of Pompeii and Herculaneum, which were destroyed in the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius in 79 CE. The collection includes statues, both large and small, portrait busts, furniture, vases, candelabra, weights, and musical, architectural, and medical instruments. At the Penn Museum, a few of the bronzes, in addition to the Borghese Satyr, are on exhibition. Three female figures from Herculaneum are at the Trescher Entrance, and a case in the Rome Gallery is devoted to the Wanamaker bronzes and highlights some of the smaller objects.

These reproductions were becoming popular in America and were acquired by a number of American museums, particularly after their exhibition at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893, where Wanamaker might have seen them when he visited at the end of his term as Postmaster General under Benjamin Harrison. Wanamaker attended a number of world’s fairs, and their vast halls with displays of goods from all over the world certainly inspired his vision for a new kind of store. In 1871, he visited the Crystal Palace from London’s Great Exhibition of 1851, and he attended the expositions in Paris in 1889 and 1900. His huge store, the “Grand Depot,” on the site of a former train shed at 13th and Market Streets in Philadelphia, opened during the 1876 Centennial Exposition, and Wanamaker was one of the most active members of the Exposition’s finance committee.

John Wanamaker’s Travels

Wanamaker traveled extensively throughout much of his life and developed an interest in both art and archaeology. In 1896, he went on a six-month trip that took him to Europe, including Italy and Greece, to Egypt, and to the Holy Land. While in Italy, he began his first venture for the Museum, in support of excavations at the Etruscan site of Orvieto. In 1901, Wanamaker embarked upon a long voyage that led him ultimately to India. On his way home in early 1902, he spent several days in Naples and also visited Pompeii and Mt. Vesuvius. The excursion may have brought back memories of the bronze reproductions he had seen in Chicago. Perhaps thinking of the new Museum and its relatively small collection of classical sculpture, Wanamaker went to Chiurazzi. The firm’s foundry was located in the vast Albergo dei Poveri, but there were also two showrooms, including one in the Galleria Principe di Napoli, a large shopping arcade across from the archaeological museum. It is easy to imagine Wanamaker there, along with other foreign visitors, looking at samples and photographs and ultimately placing his very large order.

The WanamaKer Bronzes in St. Louis

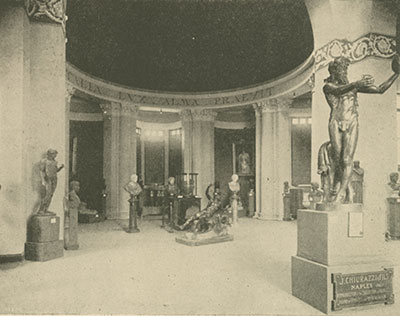

6th century BCE Greek vase called the François Vase from the Florence Museum, portraits of the Italian royal family, and copies of marble busts of Roman emperors (also produced by Chiurazzi). From Louisiana and the Fair: An Exposition of the World, Its People, and Their Achievements. ed. J. W. Buel. St. Louis 1904–1905; v. 6, after p. 2126.

The bronzes did not make their way directly to Philadelphia; rather they journeyed across America in 1904 to St. Louis. Wanamaker had loaned them so they could adorn the Royal Italian Pavilion at the world’s fair that celebrated the centennial of the Louisiana Purchase. In 1893 at Chicago, Pompeian bronze reproductions had been exhibited in the Palace of Fine Arts, along with art from many different countries. The St. Louis World’s Fair boasted a large number of foreign pavilions, where individual nations could showcase their manufacturing, culture, and art. The Italian Pavilion was the work of the Art Nouveau architect Giuseppe Sommaruga from Milan, and with its large walled garden and vaulted spaces, it was meant to recall a grand Roman villa. Contemporary commentators particularly remarked on its “Caesarian” or imperial character, an impression no doubt enhanced by the bronze reproductions adorning the pavilion’s interior. The Borghese Satyr took center stage, with Chiurazzi’s advertisement on its base. The firm’s work was shown to great advantage in this setting and introduced the reproductions to a new group of potential buyers. Orders for bronzes could be placed, and the exhibition’s catalogue noted that “Mr. S. Chiurazzi [Salvatore Chiurazzi, son of the founder] in charge, cheerfully solicits your patronage.”

The Italian Pavilion was a popular attraction, and when President Theodore Roosevelt and his wife Edith visited the Fair in late November of 1904, Salvatore Chiurazzi presented Mrs. Roosevelt with a reproduction of the famous dancing faun from the House of the Faun in Pompeii (see the Penn Museum’s reproduction of the faun on page 44). Wanamaker also visited the Fair and acquired a number of objects, including the bronze eagle that became a signature feature of his flagship Philadelphia store; the famous Wanamaker organ was also from the Fair. He acquired much of the Fair’s Egyptian exhibition for the Museum, notably the chamber of the mastaba tomb of Kaipure (see David Silverman, this issue).

The Wanamaker Bronzes in Philadelphia

When the St. Louis Fair closed in December of 1904, the bronzes were packed and shipped to Philadelphia, where they arrived early the next year. They were soon put on exhibition, and they took their place beside other casts of ancient works as well as originals in the “Graeco-Roman Section” in Pepper Hall and on the landing and stepped parapet of the central staircase. The exhibition was inaugurated in May of 1905 with a lecture in the Museum’s Widener Room delivered by William Nickerson Bates, curator in the Mediterranean Section and professor of classics. Sara Yorke Stevenson, one of most important figures in the Museum’s early history, praised the acquisitions in a local newspaper:

They enable students and laymen alike to study at home the history and civilization of foreign regions which the majority are unable to visit, and they bring to our own people the very best inspirations of the past, placing them in touch with the artists and artisans of the ancient world to which the new world is indebted for the elements of its own culture. Philadelphia owes a debt of sincere gratitude to Mr. Wanamaker.

The Wanamaker bronzes have survived more than a hundred years of the waxing and waning of interest in reproductions of classical art. While they may no longer be exhibited alongside original ancient sculpture, as stand-ins for objects for an audience who may never go to Italy, the history, size, and breadth of the collection make it an important resource for the study of both the ancient world and modern collecting. A gift of one of the Museum’s most generous early supporters and Philadelphia’s most prominent citizens, the Wanamaker bronzes, once the stars of the Italian Pavilion at the St. Louis World’s Fair, have many stories to tell.

ANN BLAIR BROWNLEE is Associate Curator in the Mediterranean Section.

LYNN MAKOWSKY is DeVries Keeper of Collections in the Mediterranean Section.